Who’s Afraid of Sabrina Carpenter?

The Alleged Pedophilic Fantasy & the Complexities of Feminine Performance

I was never a superfan of Sabrina Carpenter, but her career is one I’ve passively followed since she was on Disney Channel because my childhood best friend, Emma, was a big fan of Girl Meets World growing up. I didn’t find myself gravitating to much of her music over the years, but I always found her charming and witty, and especially recently I have found myself praising her clothing style choices. Consistently sharing photos with Emma as we discussed how much we like her aesthetic shift, and felt like she was really finding her niche with this hyper-feminine vintage vibe, that I not only appreciated but related to aesthetically.

I will say though, I was rooting for Sabrina. I had been watching from the sidelines for years hoping she would have her “blow-up” moment like her peer— and at one point, pop rival— Olivia Rodrigo. When she released Espresso this past spring, Emma and I waited patiently for the drop, chatting about it in our Instagram DMs. I hoped this first single off of her new album would follow the lead of Feather and be an upbeat, girly-pop anthem. I wasn’t disappointed when the single dropped. The song was fun and catchy, and she leaned heavily into the Bridgitte-Bardot-Pin-Up-Girl-Bubblegum-Pop-Princess aesthetic she had carefully carved out for herself.

My best friend and I texted each other, praising the song. We were probably some of the first people who listened to Espresso, with no idea it would launch Sabrina into being one of the central pop girls of the summer alongside Charlie and Chappell. But soon, the whole world was listening to Espresso, and all eyes were on Sabrina.

Though with so many eyes on you, criticism is inevitable. I was scrolling on Instagram when a reel of Sabrina Carpenter appeared on my feed. It was from one of her performances as an opening act for Taylor Swift. She was wearing her usual stage outfit featuring motifs that have come to be synonymous with her branding: a pastel pink mini skirt and corset featuring a heart shaped cut out at the chest, complete with her signature platform boots by Naked Wolfe. When I open the comment section, I was surprised to read comments suggesting that Sabrina is dressed like a little girl. At first, I brushed this off as a case of the chronically online being a loud, vocal minority. However, I would repeatedly find myself scrolling online and see similar comments on photos and videos of pop’s newest princess. I continued to think to myself that this was surely just an example of some TikTok brain worm infecting the masses.

I then stumbled across a twitter thread of people discussing how Sabrina shouldn’t perform in such a sexual way when her audience contains children. The thread starts off with Twitter user Popmvsics writing “I’m sorry but am I the only one offended? Like why is she being disgusting sexually in front of children…” above a video of Carpenter performing Juno and doing one of her implied sex positions alongside the line “Have you ever tried this one?”

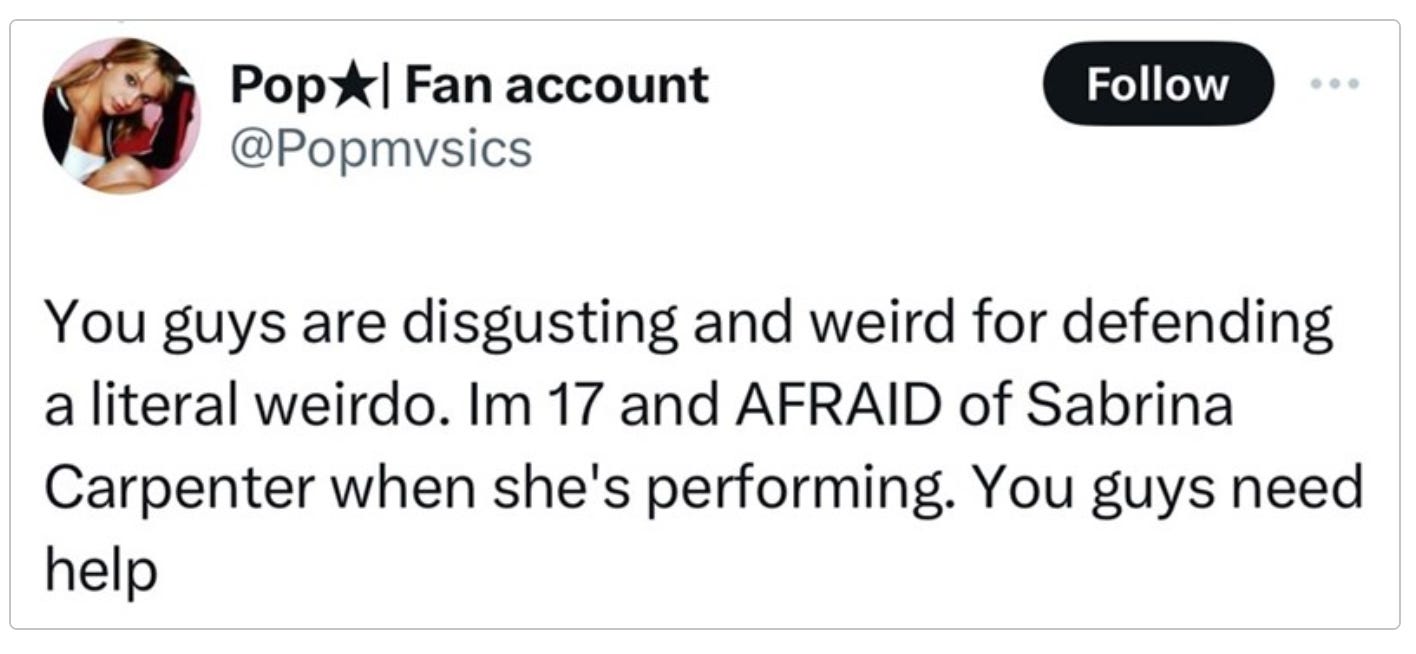

The user then follows it up with the now meme, “You guys are disgusting and weird for defending a literal weirdo. I’m 17 and AFRAID of Sabrina Carpenter when she’s performing. You guys need help” the tweet went viral, mostly of people poking fun at the absurdity in this sentiment.

A few days later, while scrolling on Substack, an essay1 caught my attention. The essay title was bold, once again declaring Sabrina Carpenter’s alleged pandering to a pedophilic gaze. This post was quickly gaining traction. Up until then I had only seen this idea suggested in comments sections without much elaboration. I was curious and wanted to understand why people were under this impression. Many people seemed to be in agreement with the Substack piece, fearful of the impression Sabrina may be leaving on culture.

So—who’s afraid of Sabrina Carpenter… and more importantly: why?

What is “The Pedophilic Fantasy”?

This idea of “the pedophilic fantasy” as used by the author of the Substack piece and echoed in these online comments, references aspects of the male gaze—a term that became an online buzzword in the early 2020s, though is often misused and misunderstood. The concept of the male gaze was first popularized by John Berger in his 1972 work Ways of Seeing2, though at the time Berger merely referred to it as “the gaze.” His ideas were later expanded on by film theorist Laura Mulvey, who would go on to coin the term male gaze in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema3.

It’s important to note that this idea of the gaze or the male gaze was first introduced in reference to the lens one would create art and media. It wasn’t just criticizing the way men inherently see the world, but rather an acknowledgement of how art and media—exclusively being made by and for men—created an echo-chamber in its expression and representation of the female form. This didn’t only reflect gender, but Berger references the intersections of race, gender, and class inherent to the idea of the gaze.

Historically (in this context), women being not the creators of art, nor the target audience, but merely incidental consumers, have in turn come to internalize this representation of the female experience as expressed by a specific demographic of men who consume women and go on to depict them for other men of a specific demographic’s consumption. Media has allowed women to consume themselves only as vessels to be consumed. Media has in this way trained women on how to best present themselves within the context of being consumed. But more specifically on how to be consumed by a very specific target demographic.

The gaze refers to not only who creates art and media but to who art and media are made for. Who is the target demographic? Women may be passive consumers of media but for much of the history of art and media women were not the target demographic of the majority of media. The male gaze in reference to art and media, as defined by John Berger, has inherently pedophilic qualities in nature. Feminine performance as shaped by dominant Western colonial culture, is deeply intertwined with infantilization, and the standard of the girl as the ultimate feminine representation rather than the woman. The pressure for women to be youthful, hairless, submissive, docile, etc are all the intertwining of the male gaze and infantilizing characteristics inherent to it. In Ways of Seeing, John Berger comments on the significance of body hair—or lack thereof—in European paintings, observing “Hair is associated with sexual power, with passion. The woman’s sexual passion needs to be minimized so that the spectator may feel that he has the monopoly of such passion. Women are there to feed an appetite, not to have any of their own.” He continues “But the essential way of seeing women, the essential use to which their images are put, has not changed. Women are depicted in a quite different way from men - not because the feminine is different from the masculine - but because the “ideal” spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of the woman is designed to flatter him.”

As women are trained since birth to perform in a way to be consumed, all women growing up in the context of consuming this media have inevitably been influenced by this gaze. And, by default this idea of the “pedophilic fantasy” also permeates our subconscious. Most women I know shave their legs, underarms, and genitals, whilst our male partners' bodies remain hairy. Many of my friends, even the academic feminists, talk to me about getting botox and filler to mitigate their smile lines and blooming forehead wrinkles. I engage in an extensive skin care routine, and obsessively wear sunscreen everyday, truthfully not because I am particularly fearful of skin cancer but because I am fearful of ageing.

The obsession with youth haunts women on a scale most men could never fully understand due to the conditioning that a woman’s value is intrinsically tied to youth. Susan Sontag writes in The Double Standard of Ageing “For women, only one standard of female beauty is sanctioned: the girl. The great advantage men have is that our culture allows two standards of male beauty: the boy and the man. The beauty of a boy resembles the beauty of a girl. In both sexes it is a fragile kind of beauty and flourishes naturally only in the early part of the life-cycle. Happily, men are able to accept themselves under another standard of good looks — heavier, rougher, more thickly built. A man does not grieve when he loses the smooth, unlined, hairless skin of a boy.”

She continues, “There is no equivalent of this second standard for women. The single standard of beauty for women dictates that they must go on having clear skin. Every wrinkle, every line, every gray hair, is a defeat. No wonder that no boy minds becoming a man, while even the passage from girlhood to early womanhood is experienced by many women as their downfall, for all women are trained to continue wanting to look like girls.”4

To express femininity is to alter oneself—and not only to alter oneself, but to alter oneself in order to maintain proximity to the standard of “the girl” for as long as possible. Nearly all expressions of femininity, as defined by colonial Western culture, can be traced back to these infantilizing standards. Culture and art is in constant conversation with themselves, and so we exist in a feedback loop of infantilized feminine performance. If I express myself in any type of feminine way I am likely referencing something that is referencing something which in turn references something rooted in this so-called “pedophilic fantasy”—a fantasy that places juvenile feminine beauty on a pedestal. The fantasy of “the girl,” as Sontag describes.

Dissecting Sabrina Carpenter’s Aesthetic

Many of the arguments I’ve seen regarding Sabrina Carpenter’s alleged pandering to a pedophilic male gaze focus on her on-stage aesthetic and branding. As mentioned earlier, she can often be seen in glittery pastels, and heart motifs—symbols that one would understandably associate with femininity in general but, more specifically, with juvenile girlhood.

There have been connections made between the aesthetic of Sabrina Carpenter to the aesthetic of Lolita, Priscilla Presley or even the fembots from Austin Powers. This comparison is being made to argue that the parallel proves that she is combining the aesthetic of childishness and sexuality. However, what is being overlooked is the true common denominator here is that these are all vintage aesthetics. And all of these characters exist within media likewise set in the time period Sabrina Carpenter is referencing: the 50’s and 60s.

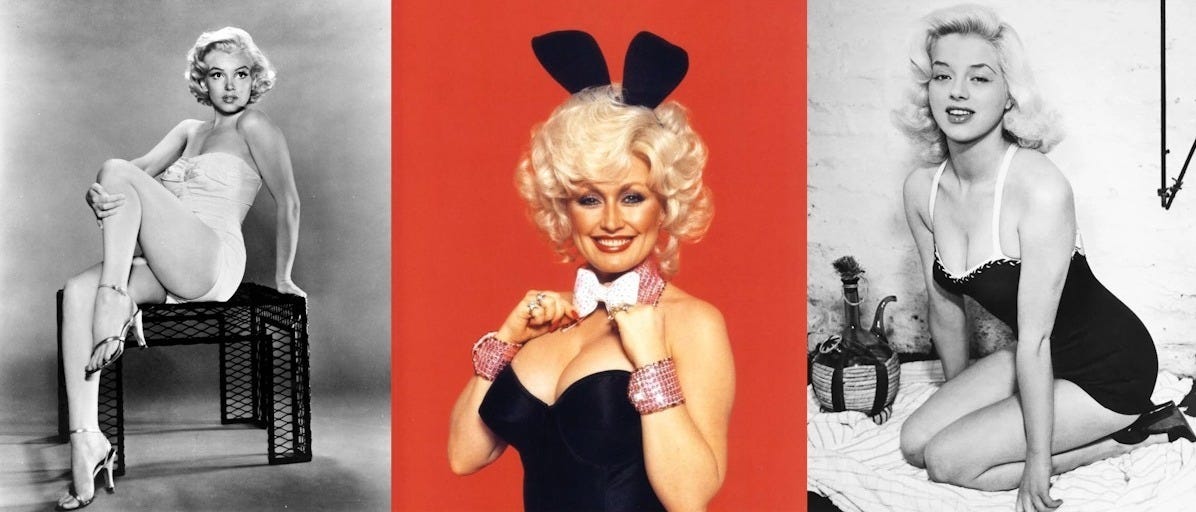

As a big fan of vintage films—especially French New Wave—I was immediately excited when I noticed Sabrina was very evidently and most obviously pulling inspiration from Bridgitte Bardot. Bardot is clearly Carpenters biggest aesthetic influence, as Carpenter has cited such alongside Jane Birkin, and Dolly Parton. Other influences evident in her style include Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfeild, Bettie Page, Diana Dors, Fran Fine, and various pinup and burlesque stars. While watching Barbarella (1968) a few days ago I couldn’t help but notice aesthetic and character parallels between Jane Fonda’s Barbarella and Sabrina Carpenter’s on-stage persona. It is evident that much of Sabrina’s aesthetic is a love letter to old Hollywood, which was further exemplified by her performance at the Grammys being a direct homage to Goldie Hawn.

Of course, many of these women mentioned above, in their hyper-feminine expression, were also likely influenced by and participated in infantilizing standards of feminine performance. This is precisely what makes the topic of feminine performance incredibly nuanced and complex to dissect. Marilyn Monroe and Jane Birkin have both performed songs in which they leaned into the “Lolita” persona, blurring the lines between girlishness and seduction. In Let’s Make Love (1960), Marilyn Monroe sings “My Heart Belongs to Daddy”, introducing herself in a hushed, girlish whisper: “My name is Lolita,” she continues, “And I’m not supposed to… play… with boys!” Moments later, the orchestra swells, and Monroe is engulfed by a group of male dancers. Although the song existed before the film, this provocative introduction was added specifically for Monroe’s performance. Similarly, Jane Birkin plays into this archetype in her song “Lolita Go Home,” referencing the same persona.

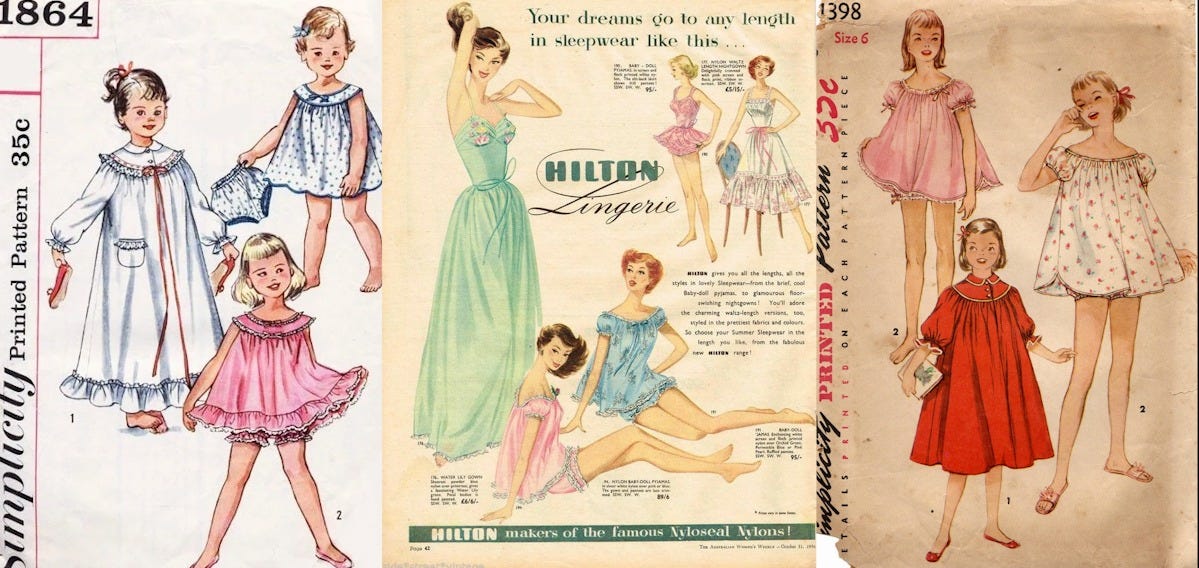

This complex intersection of infantilization and sexualization is even embedded in the names of clothing items—babydoll dresses for example. The babydoll cut is a style worn by icons such as Jane Birkin, Brigitte Bardot, Sabrina Carpenter, as well as countless everyday women, myself included.

The origin of what we refer to as the “babydoll” dress was created by American lingerie designer Sylvia Pedlar, who produced this style in 1942 as a response to the fabric shortages taking place in WWII. The name “babydoll” was popularized by the 1956 film Baby Doll. The film follows a middle-aged man’s marriage to a 19-year-old girl named Baby Doll. Despite being married for nearly two years, they’ve agreed—at her now-deceased father’s insistence—not to consummate the marriage until her 20th birthday. In the film, the couple does not share a bed and instead Baby Doll sleeps in… a crib.

Promotional material for the film featured actress Carroll Baker laying in her crib, eyeing the camera suggestively as she sucks her thumb. This film largely popularized the style of the Baby Doll dress and further pushed the use of the name “Babydoll” to describe the cut. Pedlar however disliked this name and never used it in reference to her own designs.

As we see with Babydoll dress cut, what began as a lingerie-style nightgown quickly became imbued with infantilizing characteristics—in addition to having media that reinforced these infantilizing characteristics as sexually appealing, as exemplified in Baby Doll (1956). This serves as a reminder that feminine clothing and aesthetics often have a complicated and layered history. The 1990s kinderwhore movement took the babydoll dress and intentionally subverted traditional expressions of femininity and beauty. Artists like Courtney Love used the style to mix delicate, “girlish” symbols with grungier elements—dark, smudged eyeliner, unkempt hair, and torn or oversized garments.

But the question that begs to be asked: by wearing a babydoll dress are you catering to a “pedophilic fantasy” within the zeitgeist of feminine performance?

Maybe.

This is an example of a clothing item having a blurred background in its association with infantilized standards of feminine beauty. This can likewise be attributed to many expressions of feminine clothing from ribbons, to pleated mini-skirts, to Mary Jane shoes. It’s complicated. It’s frustrating to think about, it’s frustrating to think about because feminine performance has an incredibly nuanced and often unethical past.

The Double Standard of Nostalgia

What I also find to be interesting about these conversations surrounding Sabrina—or women in general—pandering to an alleged pedophilic gaze is that it is often a conversation that persecutes women. I saw this happening a lot when the coquette aesthetic was at its peak in 2023. Suddenly, every girl was wearing baby pink and tying ribbons in their hair, on their neck, on their bags, and every other place one could manage. There felt like there was an omnipresent online discourse questioning if by wearing ribbons women were inherently and intentionally infantilizing themselves for the sake of male fetish. Many women argued that they were not. Still, the accusations persisted. Women stated that these style choices were merely making nostalgic nods to their girlhood—an act of reclaiming it through a more girlish, frivolous way of dressing.

I noticed, however, these accusations of clothing that makes nods to childhood are only ever accused of being fetishistic when on the bodies of women. I think back to the 2010s, when a particular aesthetic emerged that was very popular amongst men. It was defined by bright primary colours like those seen in a daycare, bucket hats, and childhood motifs such as Power-Rangers and Looney-Tunes on oversized T-shirts and sweaters. Overalls, often paired with striped shirts, evoked a Dennis the Menace type of style. This aesthetic was worn by and popularized by men like Tyler the Creator5 and Mac Demarco. I myself was also heavily influenced by this aesthetic in the late 2010s.

This aesthetic, despite it’s obvious nods to childhood, was never dissected or criticized for pandering to a so-called pedophilic fantasy. And whilst I was never accused of pandering to any sort of fetishistic gaze while participating in this style—despite wearing childish motifs—I have been questioned on if I am infantilizing myself or pandering to such a gaze when I have worn ribbons in my hair, Mary Jane shoes, or baby pink for example.

This leads me to believe that it is not a problem with childhood motifs on adult bodies, but very specifically girlhood motifs on women’s bodies. Why? Because boyhood is not perceived as inherently fetishistic in the same way girlhood is. And the male figure is not socially positioned as an inherent aesthetic vessel to express sex appeal in the same way the female body is.

Due to the singular standard of feminine beauty that Sontag highlights, the blurred line between the aesthetics of girl and woman creates an effect of infantilization in women, while simultaneously fostering a culture that grooms girls to perform femininity later in life. As mentioned above in reference to John Berger’s theory, the influence of the gaze has conditioned women and girls through their consumption of media to consume themselves only as vessels to be consumed.

In the same way little girls are taught early on the characteristics of “femininity” such as docility and caregiving they are also trained—often subconsciously—on how to best aesthetically present themselves within the context of being consumed. For instance, when we look at children’s clothing despite the lack of sexual dimorphism in pre-pubescent children, the clothing for girls is significantly smaller, tighter, and shorter than the clothing for boys. Restricting their ability to play and move around in favour of performing the aesthetics of girlishness. Function is forgoed in favour of femininity.

When I read the initial accusations that Sabrina was dressed like a child while she was wearing a glittery pink corset, I thought to myself—where are these people seeing children wearing glittery pink corsets? And then my mind immediately shot to Toddlers and Tiaras. Child pageantry is likewise a symptom of a culture that places emphasis on teaching girls the importance of feminine performance and exemplifies the blurring of “girl” and “woman” in regards to feminine beauty. With toddlers wearing makeup, heels, and corsets, and adult women wearing baby doll dresses, ribbons, and Mary Jane shoes, we exist in a culture where girls and women alike are taught to strive to exist as the same coveted archetype: the virginal teenage seductress. Ambiguously youthful and sexually viable.

Fetishized Starlets and Teen Dreams

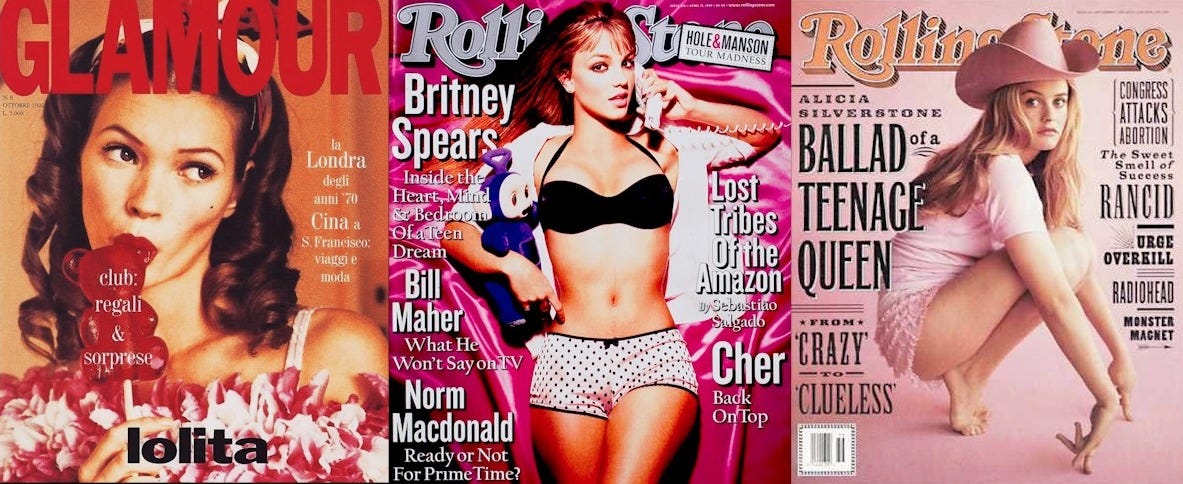

Having one’s guards up when it comes to the marketing of a young female star isn’t unwarranted. There is a legacy of studios pushing the “sexy baby” branding onto rising starlets. I am immediately reminded of Kate Moss posing for multiple Lolita-themed photoshoots in the 90s when she was a teenage supermodel. Or Alicia Silverstone posing for Rolling Stone wearing frilly pink underwear, cozying up to a pink teddy bear beneath the cover title “Ballad of a Teenage Queen.” The article opening with the line: “Alicia Silverstone is a kittenish 18-year-old movie star whom lots of men want to sleep with.” Whilst just the year before she was photographed suggestively straddling a killer whale plushie, eating a pint of ice cream in a pink crop top. Perhaps most comparatively, we have Britney Spears posing in a bra and tiny pajama shorts likewise on the cover of Rolling Stone, a Teletubby plushie in her arms as the cover disturbingly reads “Inside the Heart, Mind, and Bedroom of a Teen Dream.”

The Substack piece criticizing Carpenter for selling a “pedophilic fantasy” references a photoshoot Carpenter did for W Magazine this past September. The photo the author of the piece highlights is a photo in which Carpenter is laying on her stomach in a picturesque suburban backyard. The sun shines into frame, Sabrina is wearing a lacey white mini dress, as a backyard sprinkler doses water onto her already dampened body. This photo is undeniably a reference to the 1997 film adaptation of Nabokov’s Lolita. The Substack author aptly points this out, and further suggests this is a weird reference to make—and I agree. What complicates things is that the cinematic reference is never mentioned within the W Magazine article. This leaves us with no direct confirmation of whether Sabrina was aware of the Lolita nod or if this decision was purely artistic direction on the part of the creative team behind the shoot.

Additionally, I do want to note that the entire W piece wasn’t just a photo series of Sabrina being made to look young, or making nods to Lolita (1997). Surrounding this one weird photo making reference to Lolita, there are several other photos in which Sabrina is styled to look undoubtedly mature and womanly with stylistic motifs associated with maturity such as high collared suits, cocktail dresses, and bold cheetah print patterns. To me, this contrast further suggests that Sabrina is not making a conscious attempt to market herself as a juvenile, ambiguously youthful "teenage seductress."

The Skims campaign has also been mentioned as a point of contention. Teaming with Kim Kardashian, the campaign features Sabrina in the usual motifs that have come to be associated with her brand—lace, ribbons, and a notable air of vintage nostalgia. Criticism was raised that the set, a 90s bedroom theme, specifically evoked the energy of a teenage girl’s bedroom. This example is interesting because when I look at the Skims campaign, it’s once again not even that Sabrina is styled in a way to make her seem juvenile. In fact it takes a moment when looking at the photos to notice that it is subliminally signalling a teenage bedroom because it is a more subdued reference to adolescence than what we see in the Britney Spears shoot for Rolling Stone for example, where the set is clearly signalling child with dolls and stuffed animals, whilst Britney herself is styled in a contrasted revealing and mature outfit as the article itself boasts about her being a teenager. In the Skims shoot the only thing about the bedroom that obviously signals “teen” is the posters on the wall, and in the photos where the posters aren’t obviously in frame Sabrina just looks like herself—unambiguously, a 25-year-old woman. And yet still, the set chosen for the lingerie shoot was still decided on as being that of a teen girl, no matter how subdued it is, that is clearly the reference being made. Which of course begs the question: why?

When speaking to my friend about the Skims campaign, I asked her to help me dissect the photo because I was conflicted about how I felt. My friend pointed out that the context in which the photo is being shot matters. It matters that Sabrina Carpenter has positioned herself in a way that she is marketed as a sex symbol. It also matters that she is modelling lingerie for a brand owned by Kim Kardashian, who is known culturally as a sex symbol. So here we have two women who have this overt and intentional branding association as sex symbols positioning themselves in a bedroom that is subliminal signalling “teen girl” in order to sell lingerie. Admittedly—yes, this is a weird choice.

As suggested earlier when dissecting this idea of the gaze, demographic is important to consider. Does the target audience change how we interpret these choices? In the case of Skims, the primary demographic is women, with Kim Kardashian herself mentioning that the campaign was specifically aimed at Gen Z women and girls. In that context, the choice of a more youthful, nostalgic bedroom setting makes sense. Gen Z is a generation that is fueled by nostalgia, especially for the 90s and 00s. Given that Kim Kardashian was a teenager in the 90s, this lends itself to the 90s teen vibe of the photoshoot as she reminisces on her own nostalgia for her own teenage years as she attempts to market to a younger demographic with this specific line.

To me, the Skims campaign photos are clearly referencing something cinematic. I'm sure the creative director had specific movies in mind when they were planning this shoot but those movies were probably movies featuring teenage girls, or women playing teen girls. So it gets into this weird feedback loop where Sabrina isn’t necessarily signalling genuine adolescent imagery, but rather a caricature of teenage girlhood as expressed within cinema. This cinematic portrayal, however, is an inherently fetishized depiction of teenage girlhood. A caricature in which teen girls are often played by women in their 20s or 30s in order to satisfy the facade of the virginal teenage seductress as seen in shows like Euphoria.

This contributes to the feedback loop of feminine performance. As mentioned, when defining the original characteristics of the gaze it wasn’t just who was making the art but who the intended demographic to be consuming the art is. Historically, this audience was never women as mentioned, it was exclusively men. So, what does it say that even when the target demographic is women—as exemplified by the Skims campaign, a brand made by a woman, using Sabrina who’s primary audience is women, to sell to women— yet still we are unable to escape this influence of the gaze, and despite a lack of men in the equation we are still subliminally influenced by this need to perform their desires for them. The Skims photoshoot is a clear example of how the male gaze lingers. There is an undeniably voyeuristic tone to the images, influenced by the fact that the cinematic references being made are apart of media that contributes to the gaze, media that was made by men for men. So despite being a woman-led project with women as the target demographic, the influence of the gaze is still palpable due to the media being referenced, contributing to the feedback loop of feminine performance.

Notably Sabrina’s target demographic is predominantly women which maintains to be a consistent and evident theme in her aesthetic. Her tour notably was curated to evoke a “sleepover” energy, and to me this was successfully achieved from what I’ve seen. The clips I’ve seen from her tour remind me of going to my friends house and getting drunk while talking about relationships as we try on outfits and take photos. She simulates this experience with her fake shots, playing spin the bottle, girly costume changes, and songs about boys. There is something intrinsically feminine not just in the way Sabrina presents herself but in the space she creates and who she invites to be in it. Sabrina’s Short N’ Sweet tour has an undeniable girls night energy to, as has been described by many concert goers. It’s an atmosphere that feels deliberately built for her female audience, creating a shared experience that taps into a specific type of youthful nostalgia, rather than being curated for the male gaze, despite it’s inevitable subconscious influence.

Interestingly enough as much as I’ve seen accusations that Sabrina is catering to a so-called “pedophilic fantasy,” I’ve also seen just as many women expressing how much they appreciate her aesthetic for embodying the exact “popstar fantasy” they envisioned as children. One TikToker encapsulated this sentiment, writing: “Finally someone living out my childhood popstar dream exactly how I would’ve planned it” accompanied by footage from Sabrina’s tour. This is exactly how I felt when I saw Sabrina’s tour photos and clips. Evoking not the image of a little girl but the image of a popstar born in the mind of a little girl like Jem from Jem and the Holograms, Barbie in The Princess and the Popstar, or perhaps most aptly Hannah Montana. And this is no coincidence, Sabrina’s popstar persona was built in the mind of a little girl— her younger self. Sabrina’s pop-persona clearly is partially an ode to her inner child, in a 2020 interview6 Sabrina stated “I remember…watching the [Hannah Montana] pilot and being like ‘I want to do that. I want to sing, and I want to act, and I want to dance. I want to do all those things,’’ Rolling Stone further compared Sabrina’s aesthetics to Hannah Montana writing7 “Carpenter is the prime example of leaning into the Hannah Montana-ification of her own career and brand: in recent years, she has leaned into the high-femme styling, make-up and big blonde hair that has become her signature look when performing.” And to clarify, pulling from the aesthetics of media we grew up on does not equate to infantilization. Have we not all used shows like Bratz, Winx Club, Totally Spies, and Monster High as fashion and aesthetic influences?

There is something to be said about the legacy of female pop stars and starlets being used to push a fetishistic “sexy baby” narrative that contributes to the sexualization of teen girls. What separates Sabrina from figures like Kate Moss, Alicia Silverstone, and Britney Spears is a crucial detail: they were all teenagers at the height of these marketing campaigns. Freshly “legal” teenagers whose image was being targeted and fetishized for the sake of male consumers as was highlighted by the article titles. These girls were teenagers and freshly “legal” at the time of these shoots, and everyone involved in the marketing wanted you to know that. Fixating on their barely-legal status, and intentionally targeting them towards male consumers.

Sabrina however is, as mentioned, unambiguously 25-years-old. She doesn’t strike me as attempting to make you believe she is younger than her real age. She doesn’t look like a teen. She doesn’t style herself in a way that to me would signal that she is juvenile. She intentionally wears clothing that accentuates her womanly curves and hourglass shape. She is not trying to convince you that she is some sort of teenage sex symbol. The two controversial photoshoots—W Magazine and Skims— are worth analyzing but with context. It is important to note that these weren’t photoshoots for her own personal projects. Given her status she likely could have had some input or say in these photoshoots, though these were editorial shoots driven by creative directors and stylists with their own vision. That doesn’t absolve her of all responsibility, but it does complicate the accusation that she is intentionally pandering to a “pedophilic fantasy” and to suggest she is intentionally infantilizing herself and curating a “sexy baby” aesthetic that panders to pedophilia using these photos specifically as evidence of that is misleading.

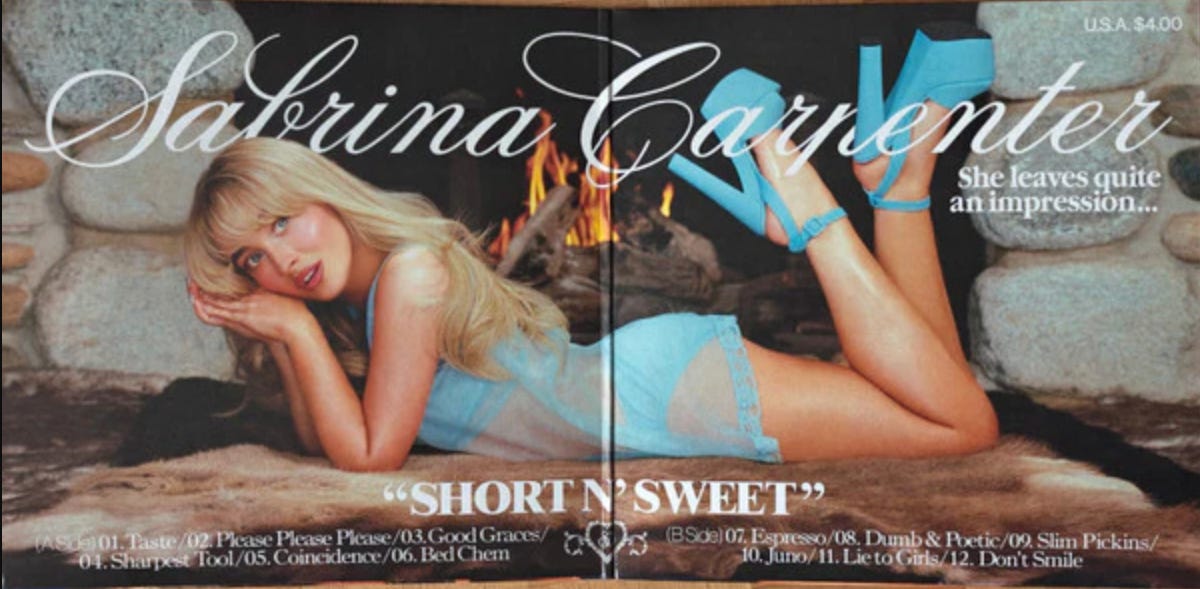

When we look at the marketing for her own material, there’s a clear distinction. In all of Sabrina’s marketing for her own material I have never seen her brand herself in a way that signals “teen” or “Lolita” In the marketing and promotional material for her own album and or specials I repeatedly see Sabrina utilize vintage and pinup aesthetics that evoke imagery of Brigitte Bardot and Marilyn Monroe—not Dolores Haze.

Sabrina notably makes no attempt to characteristically infantilize herself, which is important here. In interviews she never plays dumb, she never raises the pitch of her voice to sound more docile or girlish. In fact she speaks in a rather low-pitched voice which the W Magazine interview mentioned before made note of: “Carpenter, who is tiny, with cascading blonde hair and a surprisingly low, sexy voice-” However, Carpenter is using archetypal feminine motifs that teeter the line of “girl” and “woman”, which seems to lead to this contention. As mentioned above this line is incredibly hard to avoid when performing femininity, and Sabrina has, in many ways, positioned herself a caricature of hyper-feminine expression. It likewise isn’t as easy as just opting to not participate in feminine expression at all, because by choosing to intentionally subvert expression of femininity as defined by the gaze, you still place the gaze at the center of your expression and are ultimately defined by your proximity to it.

I have an impulse to be sympathetic towards Carpenter. Maybe it’s because I like her aesthetic, and she draws from a similar era and style icons that I have an affinity for. That I myself have always liked traditionally girlish emblems of femininity like ribbons, babydoll dresses, and Mary Jane shoes. The reality is the expression of femininity is incredibly nuanced, with a long, complex history of intertwining social issues including race, class, and the exploitation of girls. I don’t think Sabrina is trying to position herself as the “sexy baby” people are making her out to be. I don’t think she is pandering to a pedophilic fantasy. I think the examples such as the Skims Campaign and the W Magazine photo are symptoms of subconscious problems with the expression of femininity within the context of the colonial, Western, globalized culture we reside in— problems that do deserve to assessed through a critical lens. But, to be completely honest, I don’t believe that micro-managing the aesthetics of femininity is a path to liberation. And I find this entire conversation to be slightly annoying.

The author of the original Substack piece I am referencing alludes to the idea that perhaps this is all a ruse—that by allegedly infantilizing herself aesthetically, Sabrina may dodge criticism, or avoid being “woman’d,” as we so often see happen with many female stars. However, I don't think Sabrina is actively or intentionally infantilizing herself nor do I think Sabrina is attempting to shield herself under the guise of girlhood, because as we can see she is being criticized and chastised all the same. And as exemplified by teen stars such as Britney Spears, fictional girls such as Nabokov’s Dolores Haze, or the imagery seen in the 1956 film Baby Doll, girlhood has never been a safe place to begin with.

Hurley, Jade. "Your Fave Is Selling a Pedophilic Fantasy." Jade Hurley, Substack, 13 Sept. 2024

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books, 1972

Mulvey, Laura. Visual and Other Pleasures. Macmillan, 1989.

Sontag, Susan. On Women. Edited by David Rieff, introduction by Merve Emre, Picador, 2023

I am aware that by bringing up Tyler the Creator I am inherently introducing the nuanced relationship of Black masculinity and the adultification of Black children. And that Tyler’s specific expression of masculinity through a “boyish” aesthetic raises it’s own conversation surrounding the performance of masculinity for Black men, especially the over-sexualization of Black men and boys within culture. This is not lost on me, and I am not critiquing Tyler for his expression of nostalgia in fashion to be very clear.

Johns, Gibson. "How 'Hannah Montana' Inspired Sabrina Carpenter's Career: 'I Want ...'" Yahoo Lifestyle, 12 Aug. 2020, www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/hannah-montana-inspired-sabrina-carpenter-150826124.html

Spanos, Brittany. "Welcome to the Hannah Montana Generation of Pop Music." Rolling Stone, 12 Aug. 2020, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/hannah-montana-pop-music-generation-sabrina-carpenter-chappell-roan-1235051502/

I think the sentiment of Sabrina catering to a pedophilic gaze mostly comes from things out of her control. Her short face, big eyes and height are all factors that are associated with children. Also her feminine aesthetic doesn’t help, considering femininity is still seen as childish

thank you for such a nuanced take! your mention that micro-managing feminism is not a path to liberation is exactly what i’ve been feeling about this conversation. it’s important to discuss the incessant infantilization of women and the use of that to market women to men, but policing other women’s’ well-intentioned performances of femininity is a dangerous path to go down. femininity is not dangerous, but the bastardization of it is. context is the difference, which you so aptly explored