Capitalist Necromancy & the Danger of Nostalgia as Merchandise

MAGA, The Indie Sleaze Revival, Sequels, Prequels, Biopics, and Remakes.

In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.

- Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

It’s a warm summer night in Hollywood. I make my way through the crowded dodgy dive bar where the sounds of LCD Soundsystem can be heard emanating from the pulsating DJ booth. The CobraSnake weaves his way through the crowd of twenty-something-year-olds, most of which look like they could be characters in the 2007 drama Skins with their ripped tights and heavy black eyeliner. He snaps a photo of me leaning against the pillar of the bar. At the end of the night everyone gathers around outside, cigarette smoke and drunken conversation thick in the air. The DJ greets me, with her blonde hair, lacey white clothing, and girlish cadence she immediately strikes me as an Americanized Cassie Ainsworth. Behind me The CobraSnake continues to capture the evening; two young people line up against a wall, recreating the cover of the 2008 self-titled Crystal Castles album. The girls in front of me capture their own photos with their hand held digital cameras, also likely from the 00’s. One could easily mistake this scene as taking place in the 00s, though it is 2024. The scenery is almost entirely indistinguishable from the year 2008 from the clothing, to the music, to the tech being used. A crowd of young people cosplaying a time they only know the echo of. Consumed with nostalgia for an era they never truly knew, but think they would have liked to know.

Nostalgia lines the streets of Hollywood in the string of billboards advertising prequels, sequels, biopics and remakes. The target audience is often ambiguous and not clear. Are they pandering to us, or catering to the younger generation? Children today watch replicas of the media we grew up watching. The hand-drawn animation swapped for cheap looking CGI. Or animation is scrapped altogether and a half-hearted live action adaption is made. A long-passed celebrity is risen from the dead to perform amongst the influx of biopics. In a necromancy-esque ritual these celebrities and artists are risen from the grave, their corpses hoisted on puppet strings in another display of performance. Though despite the spectacle the marionette still reeks of rotting flesh. The MAGA slogan becomes more pervasive than ever as we enter Trump’s second term of presidency. A nostalgia-fuelled sentiment evoking the mythology of an idealized American past. Everywhere I look there seems to be a longing for the past in the form of advertised and commodified nostalgia. But why?

I have long been a girl consumed by nostalgia. I have often referred to myself as nostalgic to a fault, and when I was a teenager I would often make myself ill from my tendencies to soak in my nostalgia fuelled melancholy. Tears spilling on the pages of my diary over the cruel nature of the passing of time and my neurosis of romanticizing the past. Everything just out of reach always felt better than “now”. Though it would seem I’m not the only one. Gen Z has been referred to as the most nostalgic generation alongside Millennials. We are a generation consumed by nostalgic consumption. Nostalgia consumption is described as “a social and cultural trend that could be described as the act of consuming goods that elicit memories from the past, being associated with the feeling of nostalgia.” Is it us that cannot let go of the past, or are we merely being force fed the past. Like a mother bird, capitalism regurgitates the digested media of the past into our mouths and we eat it up every time. In 2024 the top 10 highest grossing films all came from pre-existing intellectual property, and over half of the six major Hollywood studios movies for 2025 will likewise pull from existing IP.1

River Quintana writes in their essay The Cult of Yesterday2 “Capitalism, it seems, can’t let go of the past. Like a necromancer, it reanimates the corpses of bygone trends, ideologies, and aesthetics, then sells them back to us at a markup. This “capitalist necromancy,” as it were, thrives on a manufactured brand of nostalgia, manipulating our longing for a romanticized past in order to justify its own uninspiring, even grotesque, existence.” they continue “Look no further than the endless parade of reboots, sequels, and revivals dominating our screens. Studios exploit our affection for beloved franchises, resurrecting them as hollow shells devoid of their original spark. These cultural zombies, stripped of their authentic “aura” (as Walter Benjamin lamented), not only generate significant profits but also divert attention from the festering wounds of the present: inequality, economic precarity, environmental devastation, and so on. In contemporary consumer culture, reality has been dissolved and replaced by a proliferation of images and simulations. Capitalist necromancy leverages our human tendency to value and desire objects of the past, transforming nostalgia into a fetishistic relationship within consumer culture. This phenomenon occurs when the object of desire—the past—becomes a substitute for unattainable fulfillment, leading to the fetishization of vintage products and rehashed aesthetics. Retro merchandise and fashion become talismans promising connection to a romanticized past, blurring the lines between reality and fabricated desire.” As previously mentioned the phenomenon of commodified nostalgia is perhaps most vividly illustrated by the current media landscape of remakes, sequels, and prequels. These works, which Quintana aptly refers to as “cultural zombies,” have become the backbone of current mainstream entertainment. This strategy often reduces these creations to hollow replicas of their original forms, stripped of the innovation and risk-taking that made them significant in the first place. It feels like every month there is announced the revisiting of an existing IP or another contribution to the ever haunting biopic industrial complex.

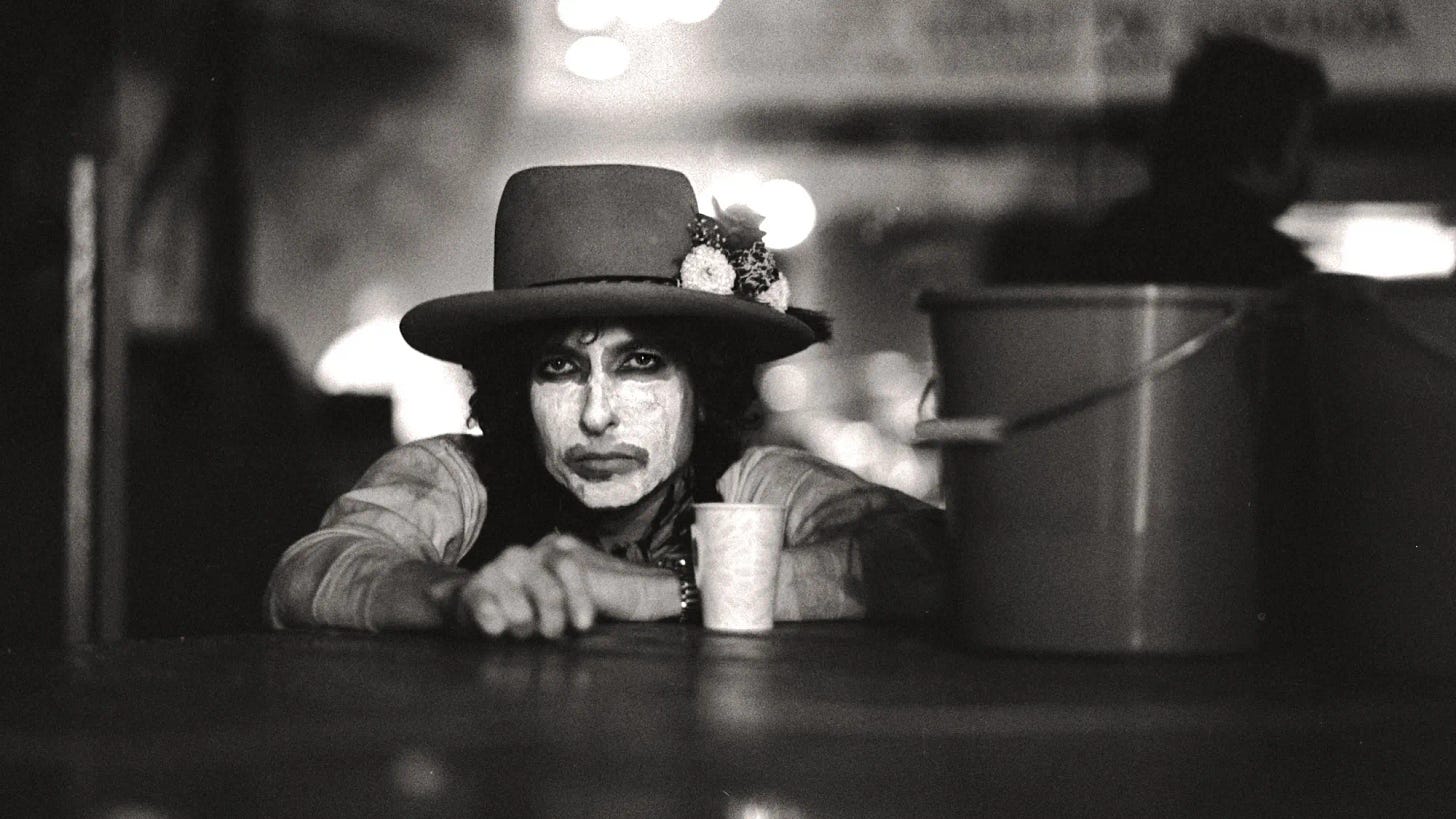

Most recently it was reported that Challengers (2024) director Luca Guadagnino is set to direct a remake of the 2000 film American Psycho, an adaption of the 1991 novel of the same name by Bret Easton Ellis. As the news articles rolled out about this rumoured remake every post I saw from my friends online was negative and unreceptive to the idea. With Austin Butler rumoured to be filling the shoes of Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman, I myself posted begrudgingly on my Instagram story “I’m going to kill myself” alongside a screenshot of a news headline advertising the alleged film. Additionally several friends of mine have messaged me at this point asking for my opinion on the prospect of Ariana Grande to play Audrey Hepburn in a biopic and every time I respond “Absolutely not.” repeatedly irritated by the idea. I’ve made a point of not seeing biopics or remakes anymore. I don’t care. Come up with new ideas, better ideas. Why would I watch Timothee Chalamet play Bob Dylan when No Direction Home (2005) and Rolling Thunder Revue (2019) directed by Martin Scorsese exist? That is a combined nearly 6 hours of footage of actual Bob Dylan directed by one of America’s greatest directors.

Baudrillard writes in The Transparency of Evil: Essays on Extreme Phenomena3 “Most present-day images - be they video images, paintings, products of the plastic arts, or audiovisual or synthesized images - are literally images in which there is nothing to see. They leave no trace, cast no shadow, and have no consequences. The only feeling one gets from such images is that behind each one there is something that has disappeared.” This sensation that Baudrillard describes is present within these sequels, prequels, remakes, and biopics. They are hollow echoes of a previous time though devoid of weight or substance. I remember when I watched the “live action” Lion King film in theaters when it came out. It was almost note for note the same as the original animated film, down to the tone many of the voice actors recited their lines. Though it didn’t leave me feeling newly inspired or with a newfound appreciation for the story. All it did was make want to be watching the original 1994 film instead. There is similar criticism being made as footage has come out from the upcoming 2025 live action adaption of How to Train Your Dragon, a remake of the 2010 animated feature of the same name. As the footage made rounds on the internet one of the primary criticisms was if you’re going to do a note for note, shot by shot, remake of the film but with real actors and different CGI techniques, is there truly even a point in remaking the film at all? No, probably not. But, studios aren’t making these films, or rather remaking these films, because they think it's a worthwhile groundbreaking concept, nor a stimulating artistic pursuit. Capitalist necromancy thrives by preying on the nostalgia you have for a piece of media you loved in your formative years. Rather than risking the investment of original concepts, studios rely on nostalgia capital.

Guy Debord writes in The Society of the Spectacle “The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point that it becomes images.”4 the influx of media preying on our nostalgia is a reflection of this sentiment. Remakes, sequels, prequels, and biopics transform nostalgia into commerce to be sold back to the viewer. It turns nostalgia into a physical tangible thing to be consumed. Lost of its original meaning, and devoid of substance as Baudrillard points out earlier on. The images of our childhood replay in front of us in the form of sequels, pandering to the child that we once were. Through this we are offered to buy back a slice of our childhood. Our memories become merchandise. Debord further states “The spectacle is not a collection of images; rather, it is a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.” What we miss is not the media itself but rather how we felt when we consumed it originally and the time in our life that is evoked by the re-consumption or the replication of such media. The childish bliss of watching early morning cartoons with a bowl of cereal, the way we felt falling in with the music of Bob Dylan for the first time, or of watching Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman perform his deranged morning routine and affectionately adding him to your list of “literally me” characters.

But likewise, we come to be nostalgic for not experiences from our own real lives, but experiences of eras, culture, and people we did not experience first hand. Like my teenage self neurotically and nostalgically musing about any time in my life that felt just out of reach, we likewise grow nostalgic for cultural eras that feel just out of reach, that we just missed out on experiencing because we were perhaps too young or yet to be born. I see this in the twenty-something-year-olds trying desperately to exactly replicate the bygone party era of the 00s retrospectively referred to as Indie Sleaze. Mark Hunter, The Cobrasnake, as if summoned from 2007 now weaves his way through partying crowds of NYC and LA, snapping his camera as the partygoers cosplay an era they did not experience. People at these parties behave almost like extras in films. They're acting like people at a party instead of being people at a party. This related to Baudrillard’s commentary on the abolition of the Symbolic, which, as Fisher explains “Led to not a direct encounter with the Real, but to a kind of hemorrhaging of the real.” in reference to reality TV Fisher further explains “did the presence of the cameras affect the behaviour of those being filmed? Such questions were undecidable, and there ‘reality’ would be elusive: at the very moment when it seemed that it was being grasped in the raw, reality transformed into what Baudrillard in a much misunderstood neologism, called ‘hyperreality’.” he continues “Yet reality TV is continually haunted by questions about fiction and illusion: are the participants acting, suppressing certain aspects of their personality in order to appear more appealing to us, the audience?”5 This reference of Baudrillard’s theories of hyperreality applied to reality TV can now be witnessed off screen in the party scenes of LA and NYC. As party photographers roam, and everyone armed with a smartphone in their pocket or a digital camera in their bag, this surveillance leads us to behave in a distorted manner.

We don’t just crave the aesthetic of Indie Sleaze but rather the lifestyle that we perceive these people to have when we reflect back on these images. Indie Sleaze being representative of a projected carefree time. A time before the pervasive presence of social media and cell phones. The perceived freedom and carefree culture that seemingly came alongside this is in stark contrast to our ever increasing surveillance state culture. Many of the people engaging in this replica of Indie Sleaze culture never experienced a world before the influx of computers and cell phones. To always be at risk of being recorded. Of becoming a viral moment. Even in the Cobrasnake party photos the people are much more poised in this era of the Indie Sleaze Revival in contrast to the original Indie Sleaze Era. Contorting themselves into modelesque poses which is in stark contrast to the feral partygoers of the 00s. Resulting in the photos from the Indie Sleaze Revival looking less like messy party photos and more like an editorial photoshoot with an “indie sleaze” theme. Fredric Jameson writes in Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,6 “We are condemned to seek History by way of our own pop images and simulacra of that history, which itself remains forever out of reach.”

The Indie Sleaze revival offers us not a re-living of the original Indie Sleaze era, but rather a simulation of what the original Indie Sleaze era seemed to be. An imitation of the fossilized imprint Indie Sleaze left on culture through its digital footprint. Though the fossil itself is not an all encompassing nor entirely accurate portrayal of what has been fossilized, and an imitation of a fossil is not an imitation of the life form that has been fossilized. It lacks the life, the colour, and the true essence. What we have been left with instead is a cold, hard, remnant of what once was. A soulless imitation of what we can expect things must have been like based on the fossil it has left behind. River Quintana writes “Capitalist necromancy thrives on constructing ideological fantasies around nostalgia, presenting a distorted perception of history that inspires sentimental longing for a time that never truly existed. This construction of nostalgia serves as an ideological fantasy that perpetuates the illusion that capitalism is the solution to our deepest desires and aspirations. By carefully curating imagery and narratives, capitalism creates a hyperreal nostalgia that obscures the contradictions of capitalism and reinforces its supremacy. We're lulled into a comforting loop of the familiar, the past repackaged and resold, effectively anesthetizing our critical faculties.”

And this showmanship is something I catch myself doing. When I see Mark Hunter, the Cobrasnake, at a party, camera in hand, I become consumed by self surveillance. There is an internal pressure to perform for the camera, to perform the role of the Indie Sleaze party goer because you know these photos may end up on cobrasnake.com and then social media, ready for consumption. I find myself getting outfit inspiration from Skins (2007-2013) characters. The sounds of LCD Soundsystem and Crystal Castles can often be heard pulsating through my own headphones, and I too carry around a 2007 digital camera and a 2008 sony camcorder wherever I go. I find this phenomena so interesting because it’s a culture I am witnessing but also actively apart of. On a phone call with Mark I asked if he finds it strange, having gained popularity in the original Indie Sleaze era, to witness the era of his youth and rise to prominence replicated so meticulously by the younger generations, Mark answered “I think it’s a good sign for the culture, because as much as you wanna say it’s about the music, the fashion, the this- I think it’s a really important thing to touch on how, for me at least, it feels very welcoming. You can express yourself how you wanna be… Whereas what happened [in the 2010s] with the ‘Kardashian effect’ and what they call the McBling [in the 00s]. Where everyone had to be pretty, and tan, and buff, and have tons of makeup on all the time or whatever, this ‘Indie Sleaze’ is the exact opposite. You can dress the way you want, you can act the way you want.” Mark further acknowledged this self aware performance in the Indie Sleaze Revival “Sometimes I can really tell, and then other times I’m catching a moment that they are acting for me, but I don’t realize it. That’s always been the funny thing, is that I’m there really trying to capture the true essence of something but parts of it can definitely end up being performative. It’s almost unavoidable.”

I then asked Mark if he noticed this same performative nature in the original Indie Sleaze era, or is the intense level of self surveillance perhaps the main dividing factor between the original era and it’s revival. That the Indie Sleaze Revival is a filtered version of what was defined as an unfiltered culture. Mark agreed that the increased level of self-surveyed performance is unique to the current generation though attributed to the return of the messy era being in it’s “infancy stage” stating “What was forced upon us from the Facetunes and the Kardashian effect of 2015 is burning off more and more. So, the messiness is coming back it’s just taking a while.” further stating “[but] the early 00s… it was more pure, and it was more real.”

Though is the nostalgia culture we currently reside in truly unique to the current generation, or are we merely partaking in an inevitable nostalgia cycle where we long for a time that was just out of reach? In the 1993 essay titled The Nostalgia Gap7 Tom Vanderbilt poses the same question, though within the context of the 90s. Vanderbilt writes “The process of 1970s nostalgia is a much wilier creature, as are its consumers. Whatever the current parlance—13th Gen, Twentysomething, Generation X—here is the generation that was thrust into the zenith of political and social upheaval in the United States in the twentieth century, only to wilt in the merciless apolitical drought which followed. They shrugged off the liberal and conservative crackups and read vague references to the fiscal orgy they were told was bankrupting their future." They continue “We find ourselves in the strange condition of time sped up—a shrinking of the future to look back on the past. The rise of a global media network means that events, styles, trends, fashion and other sources of future nostalgia are disseminated instantly, and as each new trend is promoted and participated in, a previous one is made obsolete. Culture, like technology and consumer goods, is now run on an assumption of planned obsolescence.”

These reflections that Vanderbilt poses in this essay are nearly identical to the ones in which I am posing here. One may be inclined to deduce from this article that perhaps we have just always been nostalgic and will always be nostalgic. The increase in the pervasiveness of nostalgia is merely an illusion. Though I would argue this is untrue. That both Vanderbilt and claims made today are accurate in our assessments of nostalgia as an increasingly prevalent and preyed upon sensation experienced within us. When Vanderbilt suggests that time was speeding up in the 90s due to the rise of global media networks, his assessment is not wrong just because we say the same thing today, contrasting the 90s as a slower paced experience compared to our lives today. If you were in a train that was endlessly increasing its speed as it moved forward, those who first noticed that the train was increasing speed rapidly within the first 5 minutes wouldn’t be wrong in their observation just because an hour later more people noticed this rapid acceleration that is now even faster than it was when it was initially pointed out, and vice versa. Both would be apt in their observation of the acceleration of the train, and neither is more or less accurate due to the other's observation. In the same sense as Vanderbilt points out— as the world seemingly gets increasingly smaller with the influx of social media continuously feeding us trend cycles at an increased rapid pace, and our illusive need for nostalgia is inflated with this acceleration.

Baudrillard reflects on the impact of images as “the meticulous reduplication of the real, preferably through another reproductive medium, such as photography”8 in response to Baudrillard sentiment Vanderbilt writes “i.e. more real than the real itself. The search for the real, in Baudrillard’s phrase, is no more than ‘a fetishism of the lost object.’” We see this in the desperate attempts to replicate the Indie Sleaze era as seen in photographs of the time. Youth search for the “real” that seems to be captured in Cobrasnakes photographs, though in doing so merely fetishize the lost object as Baudrillard expresses. Baudrillard further writes “When the real is no longer what it was, nostalgia assumes its full meaning” and so as we come to embody this fossilized replica of what once was, we grow to be consumed by nostalgia in the place of experiencing reality. Culture has become an ouroboros, continuously consuming itself.

It is November and I had freshly arrived in New York City, the beaming sun instilling a false sense of optimism in me as I make my way to the voting booth with my friend, Jackson. His phone was ringing all day, his friends and family asking him for his thoughts on who will win the election. It’s all anyone could talk about, obviously. That night Jackson and I stayed up to watch the election results and as they poured in our optimism faded with the setting warmth of the fleeting November sun. At some point I fell asleep on Jackson’s chest. I was lost to slumber when I was suddenly beckoned into consciousness by a familiar cadence on the TV. I could smell Jacksons cigarette smoke pooling in the air as he puffed away, watching the screen. With my eyes still closed, and only half awake I listen the speech on the TV, at first thinking Jackson is watching old footage of Donald Trump. Then I hear it. Trump in his undeniable cadence reciting his slogan into the mic “We can make America great again” my eyes shoot open, I am immediately awake. On the TV I see, not “2016” but “2024” written across the pedestal.

As we newly enter Trump's second term as president, it is apt to note the way in which Trump has used nostalgia to mobilize voters. A man who’s campaign ran on the nostalgia fuelled slogan “Make America Great Again” a slogan that evokes the imagery of a so-called golden-age of America, an America that was prosperous and stable. However this is an America that never truly existed, rather it exists merely as a romanticized, nostalgic, fantasy. This slogan is left intentionally vague, allowing his supporters to project their own version of an idealized past onto the campaign.

Vanderbilt similarly reflects on this in regards to the Reagan presidency “Nostalgia is a form of propaganda, an exercise in laughter and forgetting, in which the right visual iconography and perceived authenticity can create a longing for an existence which is no longer possible and was in fact never possible. The popularity of the Reagan presidency amongst younger voters was driven by this manufactured nostalgia, as his White House “character” was based on a mixture of the unfettered Cold War hardliner, the tough lawman of Hollywood Westerns, and a traditional religious “family man.” The fact that he was twice-divorced and rarely attended church seemed a peripheral issue. As Garry Wills argued, the power of Reagan’s appeal lay in “the great joint confession that we cannot live with our real past, that we not only prefer but need a substitute. Because of that, we will a belief in all his stories.” We see this same phenomenon occurring in the Trump campaign and the rise of voters charmed by this notion of “returning to simpler times” and “restoring America to its destined greatness” through Trump's projected traditional value system. This strategy mirrors Reagan's own appeal during his presidency, as Vanderbilt suggests. Like Reagan, Trump offers not a vision for a complex and uncertain future but a comforting mythology, a narrative that rejects the messiness of historical truths in favour of simplified archetypes. Mark Fisher similarly reflects on this political aspect of nostalgia in Ghosts of my Life, he writes:9

“The slow cancellation of the future has been accompanied by a deflation of expectations. There can be few who believe that in the coming year a record as great as, say, the Stooges’ Funhouse or Sly Stone’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On will be released. Still less do we expect the kind of ruptures brought about by The Beatles or disco. The feeling of belatedness, of living after the gold rush, is as omnipresent as it is disavowed. Compare the fallow terrain of the current moment with the fecundity of previous periods and you will quickly be accused of ‘nostalgia’. But the reliance of current artists on styles that were established long ago suggests that the current moment is in the grip of a formal nostalgia.

It is not that nothing happened in the period when the slow cancellation of the future set in. On the contrary, those thirty years has been a time of massive, traumatic change. In the UK, the election of Margaret Thatcher had brought to an end the uneasy compromises of the so-called postwar social consensus. Thatcher’s neoliberal programme in politics was reinforced by a transnational restructuring of the capitalist economy. The shift into so-called Post-Fordism – with globalization, ubiquitous computerization and the casualisation of labour – resulted in a complete transformation in the way that work and leisure were organised. In the last ten to fifteen years, meanwhile, the internet and mobile telecommunications technology have altered the texture of everyday experience beyond all recognition. Yet, perhaps because of all this, there’s an increasing sense that culture has lost the ability to grasp and articulate the present. Or it could be that, in one very important sense, there is no present to grasp and articulate anymore.”

Mark Fisher, Ghosts of my Life

Defined by sequels, prequels, biopics, remakes, MAGA, and The Indie Sleaze Revival we are in an era consumed by nostalgia and therefore consumed by the past. With the increase of economic instability, climate change induced environmental disasters, and still experiencing the impacts of the COVID pandemic, the future seems uncertain and bleak so understandably we rely on the romanticizing of the past for a sense of comfort. Nostalgia offers us a numbing sense of temporary reprieve, however this retreat risks becoming escapist, locking us in a loop where the past is continually rehashed rather than used as a foundation for progress or critique. River Quintana concludes “Capitalist necromancy feeds on our perpetual pursuit of unfulfilled desires. By commodifying nostalgia, it offers the illusion of satisfaction through the consumption of simulated experiences and hyperreal replicas of the past. The result is a meticulously constructed theme park of history, sanitized and curated, erasing the complexities and struggles of the actual past. While these simulations provide a semblance of fulfillment, they ultimately perpetuate the insatiable nature of desire within the capitalist system. In this way, capitalism reinforces the cycle of consumption and sustains its own ideological stranglehold.”

The complexities, struggles, and nuances of the past are not just erased but replaced with a simulacrum designed to evoke emotional satisfaction while avoiding discomfort or critical reflection. In a culture that seems to increasingly sell our memories back to us as merchandise in this era of commodified nostalgia, a carefully curated spectacle that prioritizes what is marketable and palatable over what is authentic or innovative. How can we expect to move forward when we are being consumed by the past?

Whitten, Sarah. "Box Office 2025 Movies: Existing Intellectual Property Dominates." CNBC, 6 Oct. 2024.

Quintana, River. The Cult of Yesterday: Capitalism, Necromancy, and the Dark Side of Nostalgia. 2024.

Baudrillard, Jean. The Transparency of Evil: Essays on Extreme Phenomena. 1990.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. 1967.

Fisher, Mark. “Hauntology, Nostalgia and Lost Futures.” Interview by V. Mannucci and V. Mattioli, Blackout, 2019.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. 1989.

Vanderbilt, Tom. "The Nostalgia Gap." The Baffler, no. 5. 1993

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Hyper-realism of Simulation (1976),” in Art in Theory 1900–2000 ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Woods (Blackwell, 2003), 1018.

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. 2014.

This is a strange dissonance, fiction may have very well stopped evolving because the perception of reality has already surpassed it.

The late-stage repackaging of nostalgia acts as a controlled regression, a way to cling to the simplicity of the past while distracting us (those who are old enough to remember the times) from the uncertainty of the future. It placates the bleakness of uncharted waters ahead. This phenomena has been creeping for quite some time, think the 90s artist and rockstars on tee shirts.

Starkly, this all coincides with the quiet resignation of the Black Mirror writers, a show once known for its dystopian vision. Didn’t they cite it becoming too “bleak” to keep writing? Has new forms of entertainment become too horrifying or uncanny for audiences to digest? Have we reached a point, much like The Simpsons once did, where modern television and film no longer entertain the future but merely predict the world eerily beyond satire?

I thoroughly enjoyed this, and I really couldn't agree more. We seem to be living in the Twilight Zone, but then again, even that would meet the criteria for nostalgia held, yet never experienced lol. Wasn't born yet. But without a skipped beat, there's another reboot for this and that. (e.g. another damn Final Destination, AND another Saw movie). I mean come on. They alll deadddddd, literally. Stahhpppp ittttt.

Also, "fetishistic" is way easier to just read, understand, and move past..., rather than stopping to try and say it out loud for reasons unknown....more than once..🤷♂️

Anyway...thanks for posting, this was solid. 🤙