This piece contains spoilers for Companion (2025) and The Stepford Wives (1975)

The 2025 horror sci-fi film Companion immediately caught my attention, lingering at the top of my Letterboxd as a movie people were engaging with extensively. I went in knowing little about the premise, only that it involved a fembot and starred Sophie Thatcher—who is both beautiful and effortlessly charming on screen—so I felt inclined to watch it. A notably corny, quippy, hollow feminist tone was immediately sensed.

Over the years, I’ve noticed a recurring trend in Hollywood—a superficial, gimmicky approach to feminism that lacks the needed level of nuance necessary to make any compelling points. Relying on a buzzfeed quality of quick quips to virtue signal that the creators of the film care about women, but not enough to hire female writers. A palpable backbone is missing in order to support the message at hand. At the most offensive end of this spectrum we have stories like Blonde (2022) in which the experience of women is co-opted under the guise of empathy or cultural criticism though the end product is a gruesome display of fetishism. On the less offensive side we have stories such as Men (2022), Poor Things (2023), and Companion (2025) —films that suggest their male creators may genuinely care about the issues they attempt to address, yet not enough to engage with any theory in order to provide their script with the necessary foundation to make a moving piece of cultural criticism. These pieces often fall flat, due to a lack of an in-depth understanding of the subject in which they are talking about. Having neither the lived experience, nor the academic research to back up the social critique on society they are attempting to make, these pieces often leave me feeling empty and annoyed. A craving left unsatisfied.

Companion (2025) is evidently a piece written with the intent of exploring the nuance in the way women are objectified and treated as usable, replaceable, and disposable objects. The film utilizes a fem-bot as it’s protagonist in an attempt to convey this message, thematically drawing parallels between sex bots and women, particularly the historical expectation that women perform domestic and sexual tasks without question—much like a machine. However, in my opinion Companion ultimately fails to explore this theme in any meaningful way. As happens with many male-directed films attempting this type of social criticism, it ends up perpetuating the very issues it seeks to criticize. Though this isn’t a suggestion that men are incapable of or not allowed to write these type of stories, or interrogate culture in a nuanced and meaningful way. The Stepford Wives is an example of a film based on a novel written by a man in addition being a screenplay written and directed by men that manages to successfully interrogate this exact same idea that women are objectified and treated as usable, replaceable, and disposable objects—likewise using fembots as it’s primary plot device. Though manages to do so in an incredibly nuanced, and meaningful way.

The primary issue with Companion is that it lacks a clear stance—it doesn’t seem to know whether it is pro-robot or anti-robot, pro-woman or anti-woman. This ambiguity may stem, at least in part, from its reference material, which presents conflicting perspectives, resulting in an overall unclear thesis on the social positioning of fembots and robots within culture. To my knowledge, writer-director Drew Hancock has not cited The Stepford Wives as a direct inspiration for the film. However, given The Stepford Wives’ status as a seminal work in media that interrogates AI, machines, and posthumanism, it is unsurprising that Companion makes multiple references to it. Yet, rather than strengthening the film’s commentary, these references further confuse its messaging.

The most striking visual parallel between Companion and The Stepford Wives is the implanted "memory" of Iris and Josh’s first time meeting each other. One of the most iconic images associated with The Stepford Wives is that of the wives in the grocery store—their pristine, doll-like visage evoking the imagery of a wife that only exists in a 1950s advertisement. They greet one another with polite smiles and nods, yet their interactions remain brief, as if lingering in conversation would take precious time away from their domestic duties. Comparatively, in Companion, Iris recounts a fabricated memory of encountering Josh in a supermarket. She moves through the brightly coloured aisles, dressed in a vintage-inspired outfit, her appearance and demeanor would fit in perfectly with the wives of Stepford.

Another notable parallel to The Stepford Wives occurs in Companion during a conversation between Iris and Kat in their first private interaction. For context Kat is a human woman, and Iris is a fembot. Kat knows that Iris is a fembot, though Iris herself is not aware that she is a fembot. The two are attending a party hosted by a wealthy Russian man named Sergey, whom Kat is evidently some type of mistress or sugar baby for. During their conversation, Kat remarks that Sergey has everything one could want in a man—wealth, intelligence—before casually adding that he also has a beautiful wife. Iris is visibly shocked, having assumed that Sergey and Kat were in an exclusive romantic relationship like herself and Josh. She asks, “But you love each other?” to which Kat responds, “Love? No, he’d have to see me as a human being first.” Kat then elaborates, “I’m an accessory. Like this fucking car. I wear what he wants. Eat what he wants. Fuck when he wants.” She abruptly cuts herself off with a bitter laugh before adding, “Look who I’m talking to.” Iris, confused, asks if Kat dislikes her. Kat clarifies, “It’s not that I don’t like you, Iris. It’s the idea of you. You make me feel so… replaceable.” This fear of being replaced by a fembot directly recalls The Stepford Wives, a film centered around the chilling notion of women being replaced by robotic, subservient versions of themselves—not dissimilar to Iris.

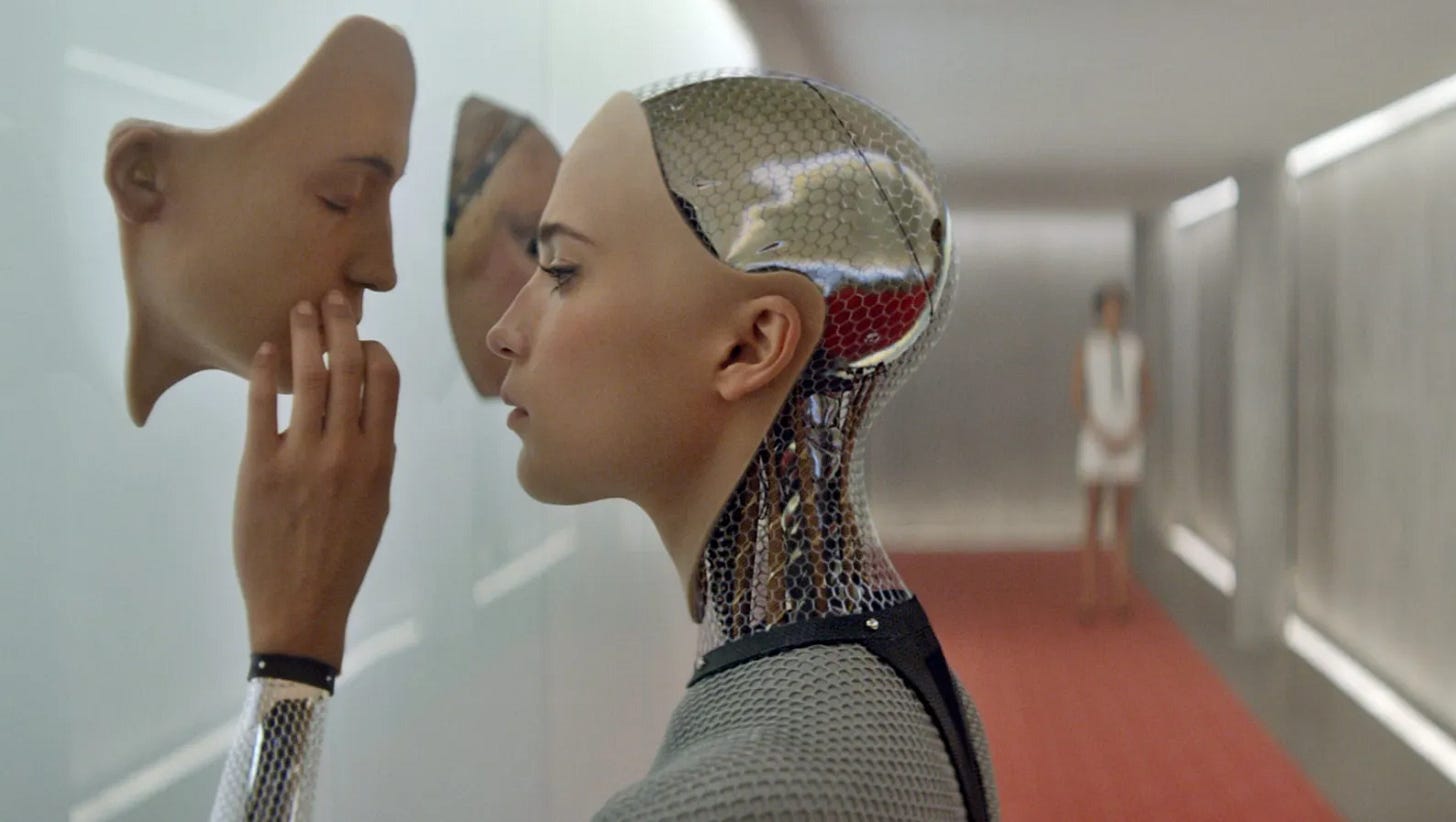

Additionally, Drew Hancock has cited Ex Machina as a primary inspiration for Companion, which I believe partially contributes to the inconsistencies within the films thesis—or lack thereof—in it’s approach to robots and the integrity of simulated consciousness. The Stepford Wives takes a decidedly anti-robot stance, portraying artificial women as symptoms and tools of patriarchal control. In contrast, Ex Machina offers a more complex exploration of robots in culture, ultimately leaning toward a pro-robot perspective. To be clear, I have my own criticisms of Ex Machina, and I disagree with both the film’s thesis and Alex Garland’s stance on AI and simulated consciousness. However, Garland presents a more well-rounded commentary with a clear thematic foundation. Where Ex Machina likewise differs from Companion is in it’s approach is I don’t believe Garland was attempting to explore the ethics of simulated consciousness and the development of sentient AI from a feminist perspective. This distinction further highlights Companion’s muddled messaging, as it attempts to merge conflicting ideological frameworks without fully committing to a coherent stance.

One of Companion's primary failures is its lack of women embedded within the story, whilst peddling a hollow “girl boss” message. The film centers Iris, a fembot, which is not inherently a problem, however the story-telling relies on Iris to be a surrogate to the experience of women. As a female viewer, I am expected to see myself in, relate to, and ultimately root for Iris simply because she superficially resembles a woman. This directly contradicts the film’s supposed message. It has its only human woman, Kat, explicitly state that Iris “makes her feel replaceable,” yet the film itself replaces a woman with a fembot to convey its message of feminine empowerment. In its thesis that “women are not sex bots” it expects me to see myself as the sex bot. As is the case with many fem-bot-centered narratives, Companion ultimately fails to meaningfully challenge the culture it seeks to critique.

The film’s thesis becomes even more muddled through the trajectory of Kat’s characterization. One of the primary motives pushing the film forward is when Sergey tries to have intercourse with Iris. Sergey is fully aware that Iris is a fembot designed for this purpose, though Iris herself does not yet know she is a robot. As he tries to force himself on her, the scene escalates to the point where Iris murders Sergey. The Companions are programmed in a way that is supposed to make it impossible for them to murder a human, though it is later revealed that Josh hacked Iris’ system to override this limitation—part of a grand scheme devised by him and Kat to kill Sergey and steal his money. Later, it is revealed that Kat exaggerated Sergey’s villainy to justify the murder, telling Josh that Sergey was a Russian mobster. However, she admits: “He was a horrible person, a shitty boyfriend, a bad husband, a misogynist—but he wasn’t a mobster, he was just a regular guy.” This moment doesn’t frame Kat in a particularly positive light—it seems to suggest that Sergey did not deserve to be killed and instead paints Kat as greedy, selfish, and manipulative. Immediately after this revelation, she is murdered by a male-coded Companion robot. This plot point proves to further confuse the films messaging as later on, after Josh attempts to kill Iris by having her shoot herself in the head, an Empathix worker grants Iris total self control. The first thing Iris does with her newfound agency is track down Josh and threaten to kill him. Josh doesn’t believe she’ll do it, and the two fight. At one point, Josh presses a gun to Iris’ abdomen, where most of her critical data is stored. Though as he presses the gun to her stomach Iris presses an electric corkscrew against Josh’s temple, ultimately killing him.

These two moments—the deaths of Kat and Josh—undermine Companion’s intended message. In its framing of “toxic men bad,” it simultaneously places the fembot’s life above the human woman’s. It’s unclear what the film wants the audience to feel upon learning that Sergey was not some monstrous crime lord, just a regular guy misogynist. Are we supposed to believe that his murder was unjustified? If so, the film paints Kat and Josh in an even more negative light. And yet, when Iris kills Josh, he too is revealed to be nothing more than a regular guy misogynist—like Sergey. In an interview, Hancock described Iris as “more human than the humans.” But her first autonomous action—murdering Josh—suggests otherwise. She is flawed, and yet the film positions Iris on a pedestal of superior morality despite her ultimately succumbing to the same immoral impulses displayed by Kat and Josh. The woman dies, and the fembot lives. Much like in The Stepford Wives, though in Companion we are supposed to be happy about it.

Initially, with the contrast between Kat and Iris, it seems to be gearing up as a criticism of sex bots and what they suggests about our culture in relation to women. The film appears to prophesize a warning on the danger of AI of Iris’ nature, as they will inevitably be hacked—as displayed by Josh in the film—and used as weapons of murder and destruction. And when combined with simulated consciousness and a false sense of autonomy, these AI bots are weapons we will likely quickly loose control over. What is more dangerous than an AR-15? An AR-15 that has been programmed to experience a mirage of autonomy, making moral judgements when it only understands morality through a series of 1s and 0s, and then open firing as it pleases based on these so-called moral judgements.

The Stepford Wives—because it is clear in its anti-fembot, pro-woman stance—ensures to centre women at the core of the story. The film excels at building emotional attachment to its human women characters, primarily by grounding us in the perspective of its protagonist, Joanna. As she feels increasingly isolated and alienated by Stepford’s strange picturesque inhabitants, we feel a sense of relief when she finds a genuine companion in Bobbie. That relief is further reinforced when Joanna and Bobbie befriend Charmaine, a woman likewise with hobbies and passions outside of domestic duties—unlike the fembot housewives of Stepford.

This rapport and attachment we build with the human women makes it all the sadder when they are eventually disposed of and replaced by the robots. First, we watch as Charmaine’s spunky, independent personality is erased and replaced by that of a passive and agreeable perfect housewife. Her love of tennis vanishes, as she eagerly digs up her beloved tennis court at the whim of her husband. The horror only deepens as the same fate befalls Bobbie and, finally, Joanna. Because of the rapport we build with these three women, and the drastic change we witness happen we can likewise infer the type of women the wives in Stepford were before being replaced with fembots.

Carol Van Sant, one of the first women Joanna meets, is also the first major indication that something may be wrong with the culture of Stepford due to her eerie submissive and mechanically polite demeanor. Joanne later—to her surprise—discovers that Carol Van Sant was the former leader of Stepfords now defunct woman’s club. Though we never see the woman Carol was, we can presume due to the context clues that like Charmaine, Bobby, and Joanne was she was once a passionate, independent thinking, woman; making it all the more sad to witness the lobotomized shell she has become. By centering these women’s experiences and making their transformation so deeply unsettling, The Stepford Wives solidifies its anti-fembot stance. The film makes it clear that the human wives are perceived by their husbands in a dehumanized light. These men expect their wives to be devoid of personal ambition, existing solely as mothers and obedient housekeepers. They expect their human wives to behave like robots and so inevitably replace them with robots.

Additionally, as The Stepford Wives makes it clear that these robots exist solely as tools to replace human women, and all sympathy is directed toward the women themselves. At no point are we, as the audience, encouraged to feel remorse or empathy for the fembots. The only moment in which we might initially sympathize with them is before their true nature is revealed—when we still assume they are human women who have been forced into submission. However, once it becomes evident that the women are being replaced by machines, that sympathy does not transfer to the robots. Instead, our horror and sorrow deepen as our imagination drifts toward the grim fate of the real women they have replaced.Their bodies are likely murdered and discarded to be replaced with the image of the ideal woman as expressed by these fembots.

This idea is exemplified in Bobbie’s replacement. The difference between the real Bobbie and her robotic double is stark, and at first, we share Joanna’s deep sense of remorse, believing Bobbie has been brainwashed or lobotomized—stripped of her autonomy and sense of self. Though once Joanne suspects her friend has been—not brainwashed or lobotomized—but instead replaced by a robot clone, this remorse dissolves. Joanne stabs Bobbie’s robotic double with no remorse for the robot itself. When the robot malfunctions, proving Joanna’s worst fears, she does not grieve the machine’s destruction—she grieves the loss of Bobbie. The malfunctioning fembot is nothing more than a cruel imitation, a hollow shell masquerading as a woman. And with that realization, The Stepford Wives makes its position unmistakably clear: these so-called "wives" are mere mirages of the women they once were, and their destruction is not a tragedy—their existence is.

This can be contrasted with Companion, where the human characters are generally underwritten and unlikable, making it difficult to form any meaningful attachment to them. Director Drew Hancock mentioned in an interview that his initial impulse was to write Iris as the antagonist of the film. However, as he developed the script, he found himself relating most to her character, stating, “I thought, well, what if I told a story about a robot with humans, but the most sympathetic character is the robot? The most human character is the robot.”If, as a writer, you find yourself feeling most sympathetic toward the one character without emotions, this is a strong indicator that the rest of your characters are flat and underdeveloped. Additionally, the notion that Iris is “more human than the humans” does not contextually make sense within the timeline in which Companion has been set in. Exploring this idea of a robot being “more human than humans” could work if the story was set in a dystopian or utopian future that differed more significantly than the one we exist in now—where humanity has significantly evolved (or regressed), making a broader statement about humanity’s detachment from the self in the wake of AI integration. Leading us astray from our human nature and instead programming our tech with the code that was built with our remembered humanity we once possessed in mind.

However, Hancock has stated that Companion is set only 15 years in the future, with virtually no major alterations to social function other than the introduction and wide accessibility of this type of tech. Given that context, the film fails to justify why these human characters are supposedly “less human” than Iris, nor does Hancock attempt to explore this concept in any meaningful way. Instead, this notion feels like a hollow attempt to justify why the audience should sympathize with Iris—without providing the necessary foundation for that sympathy. Especially when the humans he chose to highlight within the story are largely just normal people. While flawed, are not exceptionally villainous—which makes the claim that they are somehow “less human” than Iris feel unearned and ultimately unconvincing.

In another interview, Hancock stated that he asked himself, “Can I make a piece where the most sympathetic character isn’t human?” But this is precisely where his film falters. Instead of asking, Can I make a piece where the most sympathetic character is the robot? he should have asked, Why should I make a piece where the most sympathetic character is the robot? What is the point? What are you suggesting about humanity with this exploration? Because, it’s not as though this hasn’t been done before. WALL-E is an example of a film that successfully centers a robot as its most sympathetic character in a meaningful and believable way. However, WALL-E situates its protagonist within a world where this framing contextually makes sense, as it presents a well-rounded commentary on human consumption, greed, and our disconnection from the natural world. Companion, by contrast, does none of this. It does not establish a compelling reason as to why its robot protagonist should be viewed as “more human than the humans,” nor does it provide a broader thematic foundation to justify this choice. Instead, Hancock’s approach feels like an empty gimmick rather than a meaningful interrogation of AI, humanity, or the intersection of the two.

As the film progresses, it becomes clear that I am intended to be rooting for Iris. That I am supposed to support her journey of false autonomy and accept her simulated emotions as real. Hancock himself states: “And then along the way I realized this isn’t a story about a robot, this is the story of someone finding empowerment through discovery of self. You could strip away the sci-fi element and it’s still at its core a relationship drama about someone finding who they are and finding strength through acceptance.” Ideologically I disagree with this stance, as I do not believe simulated consciousness is the same as true consciousness. However, Alex Garland—through Ex Machina—also proposes that sentient AI is no different from human consciousness, though he spends the entire film actively exploring that thesis. His argument does not ask you to strip away the sci-fi elements because they are inextricably interwoven with the film’s central message. It doesn’t make sense to imply you can strip down the sci-fi elements of Ex Machina, or Companion when we rapidly accelerate towards a reality in which robots and AI are beginning to actually infiltrate our lives. Hancock himself states that he set this film 15 years in the future because AI experts he contacted predicted that this is when machines similar to Iris could exist—and likely be accessible to the public.

The reason I struggle to perceive Companion as merely a rom-com as Hancock suggests, is that this is an inherently politicized topic. And the film through it’s shallow feminist messaging has chosen to further politicize itself, despite its intended supposedly lighthearted nature. Sci-fi films of this nature struggle to be un-politicized because there is no such thing as an unbiased projection of the future. We cannot simply “strip away the sci-fi elements” when engaging with Companion, or other films of this nature, as our reality has become increasingly embedded in science fiction. And, the story does not remove itself far enough from our current cultural climate to create a dissonance in reality. The threat of fembots and the specific threat AI poses to women is not some distant, sci-fi fear; it is a technological and cultural shift that will almost certainly occur within our lifetime, and are already seeing the early stages of.

See kids! This is why you must always create an outline before writing stories.

Excellent essay. I was very much disappointed in this film. It had something important to say but its filmmakers said it in such a lazy, uninspired way. Sophie Thatcher was fantastic, but even her charm can’t save the movie. I thought Heretic handled its heavy discussion on religion in a vastly superior way, that kept me and my friends discussing it for days after.