I have a vivid memory of my first time online. Our bulky Windows 98 computer sat on the desk in the kitchen. I had a natural curiosity about the internet, but I didn’t understand it. I’d stand behind my older brother as he scrolled through his MySpace account in awe—until he would inevitably shoo me away. At that point, the internet felt like a distant, far away place meant for adults, like a bar or a club—somewhere I wasn’t allowed to enter.

That changed the day I received a Bratz doll for Christmas. Inside the packaging was a tiny pamphlet, and at the bottom of the pamphlet was a website: “www.bratz.com.” My curiosity overwhelmed me. I held the pamphlet in my hand and quietly plotted my infiltration into the web.

I sat at the desktop in the kitchen, staring at that icon, the icon that had tempted me for what felt like an eternity— the Internet Explorer icon in the corner of the home screen. I double-clicked it, and the browser opened. I had watched my brother do this so many times that I almost intuitively knew what to do. I moved the mouse to the white bar at the top of the screen and carefully typed in the website, using one finger to methodically ensure every letter was correct. When I was done, I pressed the “Enter” key—and an entire world exploded in front of my eyes.

As I clicked through the website, I couldn’t contain my excitement. There was a place for kids—for me—on the internet. I shouted, “Mom, look! There’s a Bratz website!” My mom glanced over from the stove. “Oh wow, that’s nice,” she said, feigning interest before returning to making dinner. She never cared for the internet or computers.

That moment marked the beginning of a childhood defined by unrestricted internet access. After clicking through the Bratz website, I thought: If there’s a bratz.com, there must be a barbie.com. Following my instinct, I typed www.barbie.com into the search bar. Once again, the screen exploded in a burst of pinks—Barbie herself greeting me on the homepage, enticing me to explore her digital space further.

Homepage. I was home, wasn’t I?

Serial Experiments Lain is an anime that has developed a devoted cult following—perhaps most aptly within the online sphere. As culture continues to move deeper into cyberspace, the messaging within Lain feels increasingly apt. The series follows a young girl’s introduction to the internet and the way it begins to blend with her life, slowly altering her reality.

Like myself, Lain finds herself online with unrestricted access—and we witness as that access begins to shift the very fabric of her life. As the series progresses, she spends more and more time online, neglecting her real-world relationships in favour of the digital space. I noticed this mirrored in my own behaviour as well: once I found myself online, my life became more and more online. All of our lives did.

And as the years passed, without even realizing it, our offline lives became meticulously interwoven with the online world. The internet—once a playground—morphed into a prison we struggle to escape.

The Information Superhighway

In Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard writes: “The imaginary was the alibi of the real, in a world dominated by the reality principle. Today, it is the real that has become the alibi of the model, in a world controlled by the principle of simulation. And, paradoxically, it is the real that has become our true Utopia—but a Utopia that is no longer in the realm of the possible, that can only be dreamt of as one would dream of a lost object.”

Here, Baudrillard describes a cultural inversion: in the past, imagination—through myths, fantasy, and dreams—was used to explain or justify reality. A world that offered us a refuge of escapism from the material world. Today, however, the situation has reversed. Reality is no longer grounded in lived experience; instead, we inhabit a culture dominated by constructed versions of reality. The paradox being that reality now feels like a lost utopia—something we have grown nostalgic for but can no longer access. We are unable to experience reality anymore, we can only dream of it, like something that has disappeared.

Serial Experiments Lain similarly prophesies and critiques this disintegration of the boundaries between the real world and the online world. As the series progresses, Lain finds it increasingly difficult to decipher reality from simulation—a crisis that mirrors our own cultural climate. Many of us express a longing for the early days of the internet—when it was a place we would enter and leave. A place where we go to escape our reality. But as time has passed, the internet has ceased to be a place separate from our lives. We work online, we play online, we socialize online. Our lives are now mediated by screens, and many of us find ourselves consciously attempting to foster that sense of separation through “dopamine detoxes,” or locking our phones away in safe-like boxes in order to try and escape the internet.

As expressed in my earliest memories of going online, the computer was confined to its intended physical space: the desk in the kitchen of my family’s home. Many families had designated “computer rooms” that housed their computer and with it—the internet. When I exited the web browser, the internet didn’t follow me out the door. Today, I carry my laptop with me on most days, and when I don’t have my laptop, I have my smartphone. When there’s no Wi-Fi, I have mobile data. The internet is no longer a place. It’s omnipresent. It’s everywhere.

In his 1995 essay Baudrillard in Cyberspace, Mark Nunes captures this shift, writing:

“From AT&T advertisements to White House policy statements, the past two years have prepared America for a changed world—or more precisely, a new world: one that exists on the shimmering surface of our computer screens. In the first six months of 1994 alone, the number of computers connected to the worldwide network of Internet jumped by one million to a total of 3,217,000 "host" machines (InterNIC). In response to this rapid growth, the media has refurbished that old American icon of both progress and freedom: the highway. Soon, every American will be back on the open road. New roadside businesses will emerge as the map of Internet continues to encompass the globe. But in its current figuration, the 'net does more than network the globe; it creates a metaphorical world in which we conduct our lives. And the more ecstatic the promises of new, possible worlds, the more problematic the concept of "the world" becomes.”

Like Serial Experiments Lain and Baudrillard, Nunes prophesizes the internet not just as a tool, but as a transformational pathway leading us to a changed reality. He continues:

“For Baudrillard, the shift from the real to the hyperreal occurs when representation gives way to simulation. One could argue that we are standing at the brink of such a moment, marked primarily by the emerging presence of a virtual world. Just as the highways once transformed our country, the "Information Superhighway" offers an image of dramatic change in American lives through a change in virtual landscape.”

In invoking the “Information Superhighway,” Nunes ties the internet to an older cultural metaphors of progress—the American highway. The “Information Superhighway” was coined as early as 1970 by Ralph Lee Smith in The Nation in an article titled The Wired Nation. Smith envisioned a future network of interconnected computers that would transform the way we work, communicate, and live. Essentially prophesizing the internet—and with it, our slow dissolution of boundaries between the real and the digital.

In Serial Experiments Lain, their version of the internet is referred to as The Wired—likely a reference to Ralph Lee Smith’s 1970 article “The Wired Nation” mentioned above. This connection becomes even clearer when Lain’s father helps her set up her Navi computer and tells her, “Communication is essential. The information highway is the key.” Both Lain’s father and Mark Nune, with their use of the phrase “information highway,” contrast the transformative nature of the internet’s integration within culture, and the way in which the physical highway system revolutionized and reshaped culture by expanding mobility, and consumerism leading to the car-centric culture of North America, and roadside business. This also led to a sense of spacial freedom and with it greater sense of physical interconnectedness.

The information superhighway acts as a similar transformation tool—though in the realm of communication and knowledge rather than physical movement. However, like the physical highway the information highway offers a similar expansion of commerce and interconnectedness in spite of any vast physical space that would have previously acted as a barrier to connection. But unlike the highway, which builds new tangible realities, the information superhighway collapses reality into pure simulation, as we see in Lain. The highway changed how people lived their lives; the information superhighway changes how people perceive life.

Lain reflects the interconnectedness of culture that emerges from the rise of the information superhighway. But this interconnectedness on the Wired—or the internet—exists as an illusion: one that paradoxically fosters disconnection offline.

On the same day that Lain logs onto the Wired for the first time, she goes to a local club called Cyberia with her school friends. While there, a shooter enters the venue. Holding a gun in his hand, he spots Lain—and either mistakes her for someone he saw the night before, or perhaps recognizes her as someone who was already haunting him through the Wired. Panicked, he points the gun at Lain and begins yelling, pleading for her to leave him alone. “The Wired can never interfere with the real world!” he cries. Lain responds simply: “No matter where you are, everyone is always connected.” Followed by the man promptly shooting himself. Spoken in her optimistic cadence, Lain's response seems at first to be a message of reassurance, though perhaps is more likely a prophetic warning or threat.

Mark Nunes suggests in Baudrillard in Cyberspace that the internet lacks the concept of undiscovered territory, as the digital terrain has already been “comprehensively mapped,” leading only to a repetition—a mere retracing of steps. He writes, “One never discovers on Internet; one only uncovers.” This idea is demonstrated through Lain’s venture into the Wired. She is never traversing new territory as Nune suggests but merely uncovering what has been laid out before her.

As Lain sits on the floor, she speaks to various phantom-like simulations. First, it is a doll. When she asks the doll to tell her a story, it offers to tell her a prophecy instead. Later, still seated on the floor, Lain speaks to a mask. The mask too speaks in prophecy, echoing the interconnectedness of the Wired. Eventually, a phantom-like simulation of her father echoes this same sentiment. A prophecy online, as Nunes suggests, is not a vision of what will be—but a retracing of what already has been. A retracing of steps from time immemorial. And like myself as a young girl sitting in front of my Windows 98 computer, Lain logs onto the Wired, and the information superhighway speedruns her into becoming a girl online—destined for a prophetic journey into digital divinity.

The Teenage Girl as the the Perfect Posthuman

Scratched into the cover of my diary in glitter-pink gel ink is a quote by Kristen Chang: “Girlhood is much like Godhood; a begging to be believed.” It’s a quote that applies aptly to Lain—a girl online who eventually becomes a god online. Girlhood, and Godhood is much like simulation; a begging to be believed.

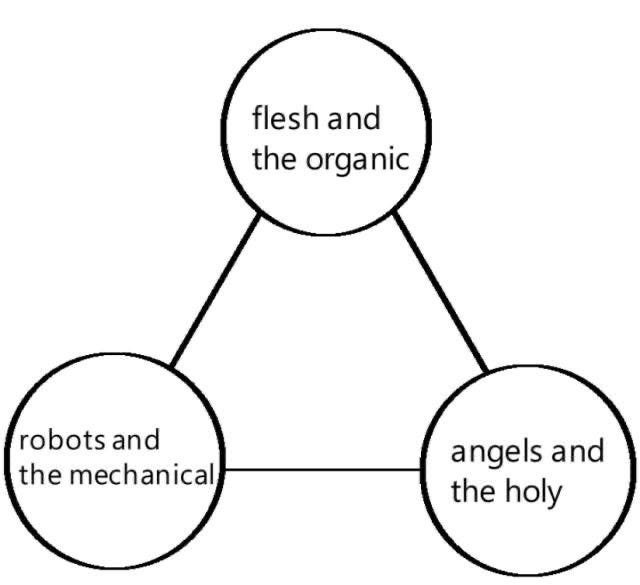

In horror young girls are often depicted as liminal figures—existing at the edge of transformation and thus vulnerable to forces like possession or divinity, as seen in The Exorcist, The Witch, or Jennifer’s Body. Though instead of a demonic force, Lain merges with the digital. She becomes the ultimate interface—a being who transcends the physical world and exists purely within the digital.

Lain is a digital chameleon, rapidly adapting and reflecting the shifting culture of the Wired. She embodies a broader cultural fixation: the girl as a liminal, receptive, and hyper-adaptable figure uniquely suited to navigating digital space. The girl in relation to the digital often acts as a conduit rather than an agent—a vessel through which tech or simulation expresses itself, rather than a master of it. Unlike male-coded cyberpunk figures like The Matrix’s Neo or William Gibson’s hacker protagonists, who “jack into” cyberspace as active agents, Lain is passive. She doesn’t conquer the Wired—she dissolves into it.

In Serial Experiments Lain, Lain isn’t just a protagonist—she’s a vessel, an interface, and ultimately, an entity that transcends human limitations. Her status as a teenage girl is essential to this transformation. Adolescent girls are cultural chameleons, reflecting back the cultural climate at hand. Teenage girls have additionally always been the creators of culture—an effect only amplified by the internet. This makes the teenage girl the ideal candidate to embody the posthuman.

Posthumanism can be defined as a transcendence of the physical body into a networked, digital form. Adolescent girls are ideal allegorical candidates for this transformation as they are already in a state of transformation, already accustomed to shifting identities and performances. Feminine performance exists already as a hyperreal expression—and this hyperreal expression only continues further down the simulacrum rabbit hole as girlhood becomes an increasingly online experience.

Lain’s evolution from a flesh-and-blood girl to a fully digital entity feels seamless because girlhood is already a space of transformation—constructed, mediated, and shaped by external expectations. The internet made girls both hyper-visible and invisible at once, much like Lain, who exists both everywhere and nowhere in the Wired.

In many ways, Lain foreshadows the climate of digital girlhood today. Young women and girls are among the most online, the most surveilled, and the most engaged in self-documentation. Growing up on the internet, our lives have been shaped by constant performance—molded by the omnipresence of social media, algorithms, and online aesthetics. In an era of beauty filters, AI influencers, and hyper-surveillance, girlhood itself has become virtual—performed for an unseen audience, optimized for engagement.

In her essay The I in Internet, Jia Tolentino writes:

“But the internet adds a host of other, nightmarish metaphorical structures: the mirror, the echo, the panopticon... Our personal data is tracked, recorded, and resold... a regime of involuntary technological surveillance, which subconsciously decreases our resistance to the practice of voluntary self-surveillance on social media... It’s as if we’ve been placed on a lookout that oversees the entire world and given a pair of binoculars that makes everything look like our own reflection.”

This idea—that we can see the entire world through the internet, but only through a lens that reflects ourselves—is perfectly embodied in Lain. No matter where Lain goes, she keeps running into herself. The more time she spends online and the deeper she ventures into the Wired, the more she encounters her own duplicates: hallways of look-alikes, gossip and rumors about herself. Persistently encountering holograms, clones, but most aptly reflections of herself on the Wired. The algorithmic digital sphere acts as an echo chamber of our own beliefs. A funhouse hall of mirrors where every corner we turn we see a distorted reflection of ourselves. The reflection staring back at us is familiar, but something isn’t quite right.

At the beginning of the series, when the boundaries between reality and the Wired remain intact, Lain’s social position is clear. She is an awkward teenage girl; her odd behaviour is understood within a framework of cause and effect. Though once Lain’s reality begins to merge with the Wired the social contract becomes fragmented as her identity does. More Lains begin to appear, it becomes increasingly confusing to decipher which Lain is the real Lain, if any of the Lains are real, or if all of them are. People's perceptions of her shift as they interact with these multiple selves. The social contract fragments as identity splinters. In Serial Experiments Lain, we watch Lain progressively lose herself to the Wired.

What happens when the self becomes so enmeshed in the digital that all distinction dissolves? When the boundary between girlhood and interface, subject and object, user and used collapses entirely?

Technology, too, often adopts a feminized persona. AI assistants and digital helpers are almost always given female names and voices. Even when technology takes on a masculine form, it is often through the figure of the cyborg—a merging of flesh and machine. The feminine, by contrast, is not integrated with technology but succumbed by tech, abandoning the flesh in totality. In this same way Lain displays an innate willingness to sacrifice her flesh in favour of the Wired.

This reflects the way in which girls so willingly abandon our own flesh in pursuit of the simulacrum of feminine performance. This takes place in the form of the ravaging nature of eating disorders, or trying experimental procedures such as botox, filler, and, ozempic without knowing the true long term consequences these may have on our bodies. As Theory of the Young-Girl states:

“From working out to anti-wrinkle creams and liposuction, the Young-Girl's determination is the same regardless—to disregard her body, and to make her body an abstraction.”

Throughout Serial Experiments Lain, Lain is repeatedly urged to abandon her body. In one scene, she sits with a phantom hologram of her mother, who says:

“The Wired might actually be thought of as a highly advanced upper layer of the real world. In other words, physical reality is nothing but an illusion. A hologram of the information that flows to us through the Wired. This is because the body, physical motion, the activity of the human brain, is merely a physical phenomenon simply caused by synapses delivering electrical impulses. The physical body exists on a less evolved plane, only to verify one’s existence in the universe.”

Later, a man who claims to be God appears to Lain and says:

“You see, I realized I had no need for a body. To die means that you have merely abandoned the flesh.”

Urging lain to abandon her own flesh. The implication is clear: the body is obsolete. A hindrance. And Lain begins to believe it. She wires herself into machines, fusing with computers until her bedroom resembles a kind of techno-womb. The man who claims to be God continues to whisper in her ear, framing disembodiment as transcendence. The body, he says, is just a machine—an outdated piece of hardware holding her back. To abandon her flesh would merely be the natural progression into the next stage of human evolution.

It isn’t until Lain’s friend Alice arrives that Lain is reminded of the importance of her body. Echoing what she’s been told by those around her, Lain insists she has no need for a body. In response, Alice takes Lain’s hand and presses it against her beating heart, insisting Lain is wrong—life, she says, is more important than progress. The messaging to abandon the flesh echoes the way in which culture urges girls to abandon their flesh in pursuit of the simulacrum of feminine performance. We’re encouraged to undergo experimental procedures—botox, fillers, ozempic—without fully knowing their long-term effects. Messages like be skinnier relayed through generations in a phantom like seance as displayed when Lain sits on the floor and speaks to a phantom hologram of her mother urging her to abandon her body. In Theory of the Young-Girl, it’s written:

“IN THE ANOREXIC YOUNG-GIRL, AS IN THE ASCETIC IDEAL, THS SAME HATRED OF THE FLESH. AND THE FANTASY OF REDUCING ONESELF TO PHYSICAL PURITY: THE SKELETON. The Young-Girl suffers from what we could call the "angel complex": She aspires to a perfection that would consist in having no body. Anorexia expresses, at the level of the commodity, the most incontinent disgust for them, and for the vulgarity of all wealth. In all of her bodily manifestations, the Young-Girl signifies an impatient rage to abolish matter and time. She is a body without soul dreaming she's a soul without a body.”

Young girls, in particular, become ideal users: malleable, receptive, always connected. Lain represents this archetype pushed to the extreme. She isn’t just the ideal digital subject—she is the perfect sacrifice. Not merely a user of the Wired, Lain is consumed by it, becoming both its victim and its god.

Digital Deities: The Intersections of Machinery and Divinity

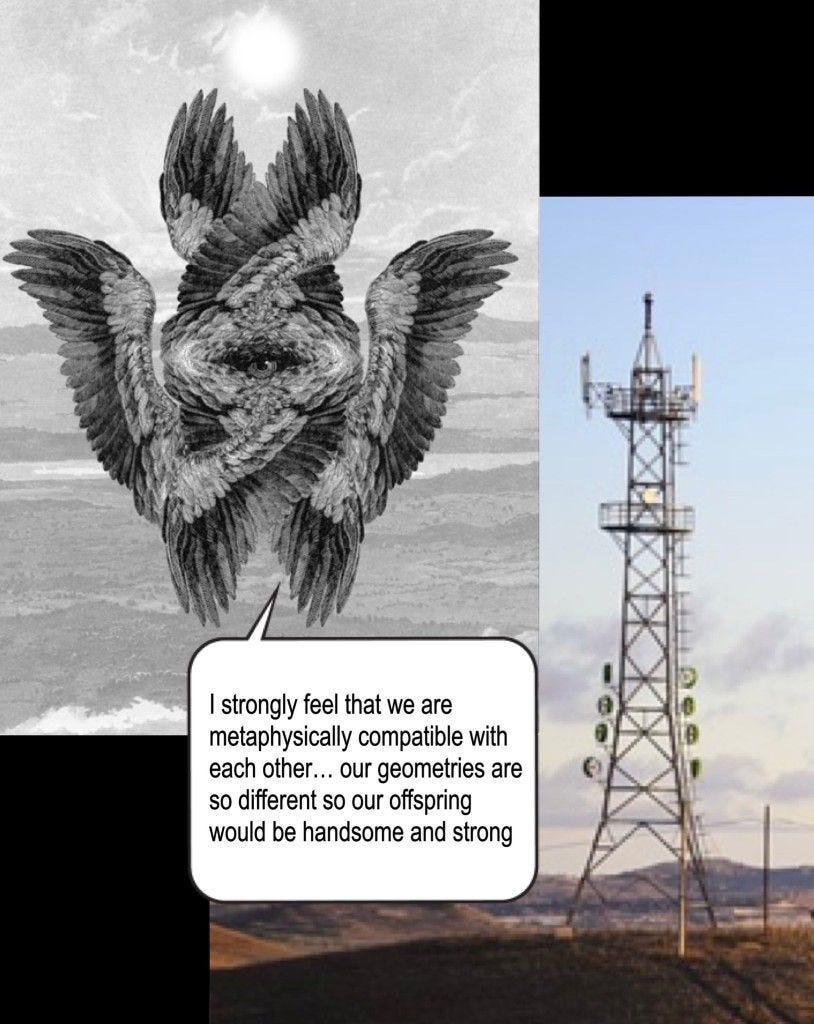

In Serial Experiments Lain, there is one thing that remains unmoving and unchanging throughout the anime: The fragmented identities and realities of Lain are carefully woven together by persistent shots of cell towers and telephone lines accompanied by the ambient humming of pulsating electricity. These wires in the sky weave together not only the story, but play an important role in connecting the physical and the online realms. The consistent use of cell towers as a transitionary shot combined with a buzzing ambient noise of pulsating electricity is apt given the parallels made between cell towers and angels. If Lain is God—or a God—then the towers serve as her angels, her divine messengers. Angels act as intermediaries between the divine and the earthly, carrying messages or acting as agents of communication. Similarly, cell towers facilitate communication by transmitting signals, and making connection between the digital and the earthly. The electromagnetic waves emitted by cell towers act as unseen ethereal messages that echo the concept of communication with the divine. Angels themselves can be understood as divine machines—constructed instruments of God’s will, simulating human form only to bridge the gap between heaven and earth. Lain is God and the cell towers are her angels—and the ambient buzzing of electricity is the hymn of worship.

In the final chapter of Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard addresses nihilism and Nietzsche’s concept of a dead God, writing: “When God died, there was still Nietzsche to say so… But before the simulated transparency of all things... God is not dead, he has become hyper-real.” Baudrillard suggests that in a culture where reality and simulation have merged, God has not simply “died” as Nietzsche suggested—rather God has become hyperreal. Existing as simulation rather than a real entity. Lain likewise becomes representative of a simulacrum of divinity. In the end of Serial Experiments Lain, Lain makes the decision to delete herself. What this means exactly and to what extent though is not entirely clear. She is no longer remembered in the vast consciousness of those who surrounded her throughout the story. And the internet, or the Wired, seems to play a lesser role in this now altered reality where Lain has been removed.This echoes Nietzsche’s “God is dead”—but unlike Nietzsche’s finality, Baudrillard’s God lingers everywhere and nowhere, a haunting presence. Inhabiting a liminal space between the real and the digital.

Lain existence as a digital deity is representative of the ultimate hyperreal girl. In many ways mirroring the influencer and e-celebrity culture—worshiped through screens, consumed via parasocial intimacy, yet fundamentally unknowable. Digital girlhood is mediated through layers of performance and self curation, a projection of an idealized self. To be seen everywhere but never fully known, idolized and erased simultaneously. Lain’s final act of erasing herself from human memory can be interpreted as a final act of shedding hyperreal performance inherent to girlhood. If she is no longer perceived, she is no longer consumed, no longer watched or expected to be anything at all. She is free.

this was a really good read. lain is my favourite show to date and ive never really seen the show been examined through a lens like this. i honestly really like this interpretation as a whole as its a lot more fleshed out (lol) than any others ive seen. great read!!

Holy moly, this is one of the best essays I’ve read here. As someone born in the 2000s, I’ve witnessed the shift from using the internet just for entertainment, maybe an hour a day, to it becoming our entire lives. Like you said, what was once something we could step away from has now become inescapable. It’s been tough to watch that transformation unfold, and yet here we are, unable to fully disconnect. Btw, Serial Experiments Lain is such a perfect example of this!